- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Emily Fridlund

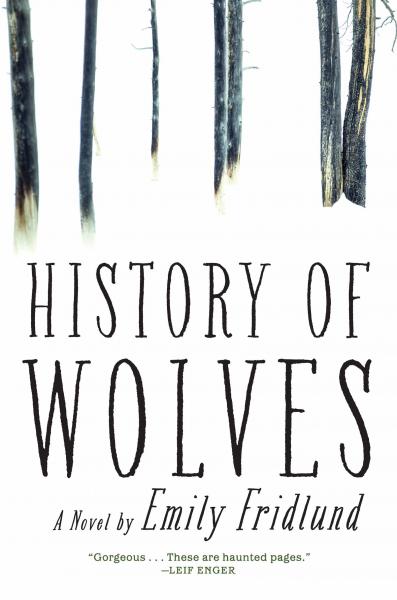

Emily Fridlund is the author of History of Wolves (Atlantic Monthly Press) a Winter/Spring 2017 Indies Introduce debut novel and the #1 Indie Next List pick for January.

Fridlund grew up in Minnesota and earned her PhD in literature and creative writing at the University of Southern California. She currently lives in the Finger Lakes region of New York and teaches at Cornell University.

Susan Tunis, events coordinator at BookShop West Portal in San Francisco, was part of the Winter/Spring 2017 Indies Introduce Adult committee that selected History of Wolves as an outstanding debut. Here, she discusses the novel with Fridlund.

Susan Tunis: Your novel has received an unusual amount of attention. It was selected as a BEA Buzz title, an Indies Introduce pick, and the #1 Indie Next List pick for January, among other honors. What’s it like to get that much attention for your debut? What’s the best part, and is there a downside?

Emily Fridlund: The attention has been disorienting and humbling. So much of these last years spent with this book I was hunched alone over my keyboard or out on rambling, solitary walks. Though I was sometimes frustrated by the work and despaired, there was — I see now — a certain innocence to that time as well. I’d been writing for so long with just a handful of readers, so I rarely thought about publication or what would happen when I finished this book. I just wanted to figure out my sentences.

Now that those sentences are out in the world, I’ve been so often moved by how readers have encountered them. It can be dislocating to think of this strange, unsettling story in other people’s heads as well as mine. At its best, it can be a little like the unexpected joy of discovering people with whom I share a mutual friend: we’ve had some of the same experiences, but not the exact same encounters, with Linda and her world. I love seeing the way readers make connections across ideas and images in the book, the way they see patterns that allow me — even after all this time — to understand the novel in ways I hadn’t quite before. That’s a best part, by far. The downside is the occasionally jarring sense of coming up against readers’ expectations that I didn’t create a different kind of book, perhaps one with a less difficult narrator or a more classic plot structure. But even this response can be enlightening, if I don’t take it too personally. I’ve always felt that the books that have stayed with me are the ones that both engage and resist my own expectations as a reader, and so it can be interesting to think more about this potentially creative tension.

ST: Your protagonist answers to Linda, Mattie, or Madeline, depending on who is addressing her. Another character, Patra, was once Cleo. Are these shifting names a search for identity or an indication of deceit?

EF: For me, the shifting of names in the novel is less about a search for identity or deceit than about a recognition of the multiple identities people are capable of embodying, sometimes simultaneously. Patra’s full name is Cleopatra, but she was called “Cleo” until she married her husband, Leo, when she changed it to “Patra” to avoid the rhyme with his name. It’s a small detail in her history, but I think it reflects a much bigger pattern of Patra adapting herself to fit into Leo’s life. Likewise, the novel’s narrator’s name, Madeline, was chosen by vote when she was born into her northern Minnesota commune. The narrator feels disconnected from her mother, who tells her she didn’t vote for this name, and, by contrast, connected to her history teacher, who calls her by a nickname that no one else uses, “Mattie.” Names in the novel became a way for me to suggest something about social contexts — how people are known and know themselves with others — rather than who characters are. To be honest, even now I find it strange to call the novel’s narrator “Linda.” It’s the name used for her most often in the book, but of course the novel is written from her perspective, so to me she is nameless, simply “I.”

EF: For me, the shifting of names in the novel is less about a search for identity or deceit than about a recognition of the multiple identities people are capable of embodying, sometimes simultaneously. Patra’s full name is Cleopatra, but she was called “Cleo” until she married her husband, Leo, when she changed it to “Patra” to avoid the rhyme with his name. It’s a small detail in her history, but I think it reflects a much bigger pattern of Patra adapting herself to fit into Leo’s life. Likewise, the novel’s narrator’s name, Madeline, was chosen by vote when she was born into her northern Minnesota commune. The narrator feels disconnected from her mother, who tells her she didn’t vote for this name, and, by contrast, connected to her history teacher, who calls her by a nickname that no one else uses, “Mattie.” Names in the novel became a way for me to suggest something about social contexts — how people are known and know themselves with others — rather than who characters are. To be honest, even now I find it strange to call the novel’s narrator “Linda.” It’s the name used for her most often in the book, but of course the novel is written from her perspective, so to me she is nameless, simply “I.”

ST: We catch only glimpses of the adult Linda narrating this tale. How much do the events related in the novel influence the woman she becomes?

EF: As a writer, including glimpses of the adult narrating this tale was essential in suggesting not only how she was shaped by the traumatic events in her youth, but also the larger range and complexity of a full life. The novel has been called a coming-of-age novel, and I do think it engages with that genre to an extent. But the coming-of-age novel often relies on a peculiarly teleological argument, one in which a protagonist (often a boy) finds his way towards increased knowledge and power through a series of events in which he loses his innocence and is educated in the ways of the world. The genre usually assumes progress, growth. But I think the process of growing up is far more complicated than that, perhaps especially for girls becoming women. It can involve a loss of power as much as its gain when young girls are educated into the histories of their country, their schools, their religions and families — when, that is to say, they are educated into the patriarchy. And the process can make a girl angry.

For Linda, briefly, the Gardner family represents a possible break from the world of her insular town and home life, the reality she was born into and which she fears will define her forever. It seems like a way out. That this break turns out to be a repetition, in a sense, of everything she has known before, of parents forcing well-intentioned beliefs on vulnerable children, and of people in positions of power taking advantage of people with less, leads Linda to attempt a kind of circular escape. She leaves home only to return, first in memory and ultimately in reality to help care for her aging mother. She is angry because there is no easy route towards progress for her, and she is guilty because of her complicity in perpetuating the traumas of this system. She understands the events of her childhood differently as a woman, but not necessarily with more clarity. This seems far truer, to me, to how it feels to become an adult.

ST: There isn’t a lot of warmth in this novel, emotionally or physically — even in summer. How much does the austere setting of the novel influence the story told — or is it the other way around?

EF: The voice and the place of this novel offered themselves to me together. Linda has been raised in austerity — out in the cold, in a sense — but she also projects that austerity onto the world around her. She is very much alone, and vulnerable, and often angry. That said, for me the cold in this novel only makes the possibility for moments of tenderness and real warmth all the more intense. The novel begins with the heat of Paul’s little body on Linda’s lap, with her memory of the everyday gift of his closeness and warmth. The very next scene echoes that desire for human contact when Linda approaches Mr. Adler, her dying teacher, and takes his hand when no one else does. Throughout the book, small moments of warmth flash (Leo hugging Linda before driving Paul away on his last day, or Rom feeding Linda oranges and salad) against the dark backdrop of this often-bleak world. For me, because of the human potential they represent, these moments are as much a part of the story as the cold.

ST: The novel’s title... Any comment?

EF: I tend to point to the opening chapter when asked about the title. Linda chooses to do her history project on wolves, even though the topic is treated with disdain by her teacher and the History Odyssey judges. She quotes Barry Lopez in her speech, saying, “An alpha animal may be alpha only at certain times for a specific reason.” The idea that power might not be fixed is one that is very compelling to an overlooked teenage girl. It promises an alternative to the more obvious hierarchies shaped by parent-child, teacher-student, and male-female relationships.

But I also like to point to the scene when Linda, sensing Paul’s sickness and wanting to buoy him near the end, takes him to see the only actual wolf in the novel: a taxidermy specimen at the Nature Center. She promises him a real wolf, but Paul says, rightly, “That’s not real.” To some extent, even Linda’s ideas about wolves are based on a conveniently curated narrative she wants to tell that resonates with the particulars in her life. Her sustaining mythos doesn’t resonate with Paul, and it can’t save him. The “history” at the heart of History of Wolves might be better described as a story, or set of stories, people tell themselves, and the wolves may be aggressors or victims, alpha or stuffed, depending.

ST: So, what’s next?

EF: Great question! I’m wondering that to some extent, too. It’s exciting to begin to think about the next project. In the immediate future, I have a collection of stories called Catapult coming out with Sarabande in October. I also have notes and jottings and a few pages of another novel idea underway, but I’ll only know more about that when I write more.

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (Atlantic Monthly Press, Hardcover, 9780802125873) Publication Date: January 3, 2017.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.