- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Hubert Mingarelli

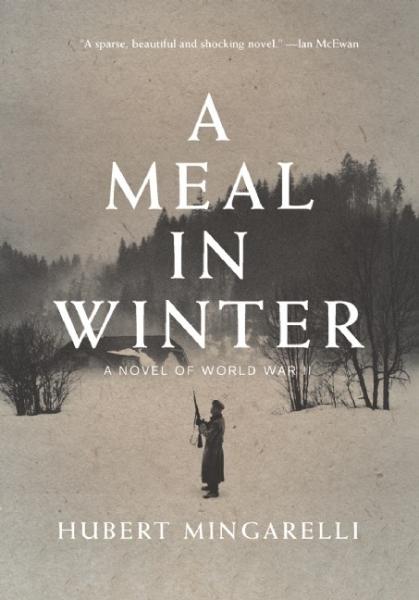

Hubert Mingarelli is the author of A Meal in Winter: A Novel of World War II, a Summer/Fall 2016 Indies Introduce debut title. Here, Sam Kaas of Village Books in Bellingham, Washington, a panelist on the Indies Introduce adult debut committee, interviews Mingarelli about his new novel.

Hubert Mingarelli is the author of A Meal in Winter: A Novel of World War II, a Summer/Fall 2016 Indies Introduce debut title. Here, Sam Kaas of Village Books in Bellingham, Washington, a panelist on the Indies Introduce adult debut committee, interviews Mingarelli about his new novel.

“Minutely observed and quietly devastating, this slim, graceful novel presents a side of the Second World War that we don’t often see,” said Kaas. “Hoping to escape the horrors of the executions their unit must perform, three German reservists volunteer to scour the Polish countryside for Jews who have escaped previous patrols. But the moral dilemma they face there will change each of them profoundly — and alter their relationship forever.”

A Meal in Winter is Mingarelli’s first book in English. His previous work includes Quatre Soldats (Four Soldiers, Éditions du Seuil), which won the Prix Médicis, an annual French literary award. He lives in Grenoble, France.

Sam Kaas: A Meal in Winter features characters whose voices are not often heard in typical narratives of World War II. How did these characters come about? What made them compelling to you?

Sam Kaas: A Meal in Winter features characters whose voices are not often heard in typical narratives of World War II. How did these characters come about? What made them compelling to you?

Hubert Mingarelli: Like most people, I’m at a loss for words when it comes to genocide. I’m unable to comprehend it. And I especially have the impression that people forget that it wasn’t just a massacre of people — it was the massacre of one person after the other, one human being after the other. Many years ago, I began to write the story of a father and his young son who were going to be executed with millions of other Jews. But I was unsuccessful. It was humanly impossible to put myself in the father’s place. So later on, I decided to discuss genocide from the executioners’ point of view. When I began this novel, I didn’t have any specific ideas — I just started with a morning, with these three German soldiers, and tried to put myself in their shoes. I was ill at ease, and I was embarrassed to tell the stories of the executioners rather than the victims. But as I delved deeper into their story, I became less uncomfortable and that was troubling. I wasn’t making excuses for them, but I was spending a lot of time with them and saw that they were simply men. These characters didn’t fascinate me, but I found them to be terribly human, no better or worse than me. At every moment in the story, I wondered what I would do in their position. I still haven’t answered that question. I still don’t understand why some men kill other men simply because they are told to do it.

SK: Did your research for A Meal in Winter take you anywhere unexpected?

HM: I actually didn’t do any research. I built solely upon what I already knew about World War II, and, like all writers, I also built on my own personal experience — I spent three years in the army, and that helped quite a bit. Of course, we never killed anyone, but I had an insider’s view of how soldiers would — or wouldn’t — submit to authority, and I saw some disobey when morality demanded it. But I realized that very few would actually dare to disobey — and it was like that for the majority of German soldiers who were ordered to kill people by the millions.

SK: The novel takes place over the course of a single day. Did you feel that this timeline was important to the story?

HM: I like stories that unfold over a short period of time — one day and one night. It seems to me that a lot of important things come to us in brief moments, and they are often events that we remember forever. I believe that the narrator of A Meal in Winter will remember this day for the rest of his life. In any case, after the three soldiers have made their decision at the end of the novel, there’s nothing left for me to say — I just have to keep quiet.

SK: Regret plays a central part in A Meal in Winter, but it’s not presented in a particularly maudlin way — in fact, the narrator’s reflections on his regrets are very matter-of-fact. Did this sort of quiet, everyday regret present itself as a theme, or do you see it as part of the reality of writing about ordinary people in trying times?

HM: The answer is complicated. The narrator says what he means, but there’s a part of his experience that he keeps to himself. He’s like me when I write — I don’t say everything. I want to leave a lot up to the interpretation of the reader. I am neither judge nor jury, and the less I say as the author, the more space I leave for the reader. My opinion no longer has value once it gets to the reader. I also think that the narrator of this story doesn’t want himself to be overemotional or maudlin — in order to protect himself from the horror of what he’s done, he has to be as detached as possible.

SK: This is the first time your work has been translated into English. What was the translation process like?

HM: I only know French, and that’s already difficult enough for me. But as with any translation, I put my full faith in the translator, who is also an author. In all parts of life, not only literature, I like to trust people.

A Meal in Winter: A Novel of World War II by Hubert Mingarelli (The New Press, Hardcover, 9781620971734) Publication Date: July 5, 2016.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As With Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.