- Categories:

A Q&A With Tommy Orange, Author of June’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

- By Liz Button

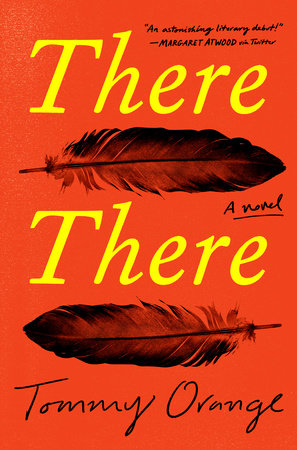

Booksellers across the country have chosen There There by Tommy Orange (Knopf, June 5) as their number-one pick for the June Indie Next List.

The novel, which is also a Summer/Fall 2018 Indies Introduce adult debut, features a series of poignant character sketches depicting Native Americans of various ages, genders, and life circumstances, most of whom live in the city of Oakland, California. The stories of these vibrantly drawn, scintillatingly self-aware characters all intersect at a local powwow in ways that are, at once, climactic, cathartic, and tragic.

The novel, which is also a Summer/Fall 2018 Indies Introduce adult debut, features a series of poignant character sketches depicting Native Americans of various ages, genders, and life circumstances, most of whom live in the city of Oakland, California. The stories of these vibrantly drawn, scintillatingly self-aware characters all intersect at a local powwow in ways that are, at once, climactic, cathartic, and tragic.

“There There is the kind of book that grabs you from the start and doesn’t let go, even after you’ve turned the last page,” said Heather Weldon, store manager for Changing Hands Bookstore’s Tempe, Arizona, location. “It is a work of fiction, but every word of it feels true. Tommy Orange writes with a palpable anger and pain, telling the history of a cultural trauma handed down through generations in the blood and bones and stories of individual lives. He also writes with incredible heart and humor, infusing his characters with a tangible humanity and moments of joy even as they are headed toward tragedy. There There has claimed a permanent spot in my heart despite having broken it, or maybe because it did. I think this may be the best book I’ve ever read.”

Born and raised in Oakland, Orange is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. He is a recent graduate from the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he now teaches writing, and a 2014 MacDowell Fellow and 2016 Writing by Writers Fellow. He currently lives in Angels Camp, California.

Here, Bookselling This Week speaks with Orange about his new book, which encapsulates different perspectives within the contemporary urban Native experience.

Bookselling This Week: Where did the idea come from to write this book?

Tommy Orange: It sort of came to me in a single moment. I was born and raised in Oakland, but I didn’t grow up in the urban Indian community there. Being Native, to me, was my dad, going back to Oklahoma to visit family, and his language because he’s fluent in Cheyenne. But then I spent a bunch of years in the urban Indian community, working in mental health, doing a storytelling project, and realizing just how many stories there were that people should hear — especially other urban Natives, to see their own stories reflected in a bigger way. We’re pretty invisible, Native people, in movies and TV shows and literature, so I was feeling like I wanted to try to tell a story that hadn’t been told about a community that people know too little about.

I had been on a powwow committee and helped put on a powwow, so the idea just dropped into my head to have a novel from the perspective of a whole bunch of different urban Native characters who all end up at a powwow in Oakland. I wasn’t exactly sure how it would end, but I had a few ideas, and they were all similar to the way it did end up. So the whole thing kind of came to me at once, and I started writing it over the next six years.

BTW: One of the book’s characters, Dene, is a documentarian who receives a grant to conduct a StoryCorps-like project to interview other urban Natives, similar to a project you did. In your view, why is it valuable to record these modern histories?

TO: I think having a strong identity as a human in general is an important thing, to feel like you belong in a certain type of community. For Native people who grew up in the city — and these are themes that work in other communities as well, but this is the one I’m from — just to hear your story or one similar to yours is powerful. It can feel really lonely to be Native but not read or see anything about being Native. It makes you feel like you don’t belong, and when you don’t feel like you belong anywhere, it creates a lot of problems. It makes it a lot harder to be a strong human being.

BTW: Have you personally felt that lack of cultural belonging?

TO: I think a lot of Native people living now struggle with authenticity. It comes from within the Native world and from outside. If you don’t look stereotypically Native, as soon as you tell somebody you are, everybody thinks they have the right to ask you how much, or how you have the right to claim that. That’s a really destructive thing to experience, whether it’s hearing it from other Native people or from non-Native people. I wanted to expand the range of what it means to be Native and what the Native experience is. Seventy percent of Native people live in cities now, and that’s been the case for the past 10 years, if not more, so to have people thinking that what it means to be Native is historical or rural and way outside of mainstream society really isolates you.

BTW: What is the origin of the title There There?

TO: In Everybody’s Autobiography by Gertrude Stein [published in 1937], she references Oakland by saying, “There’s no there there.” She’s talking about how where she grew up was all developed over and unrecognizable. As soon as I found that quote, because I wasn’t a Gertrude Stein reader or knew the quote all along, I recognized the parallel to Native people’s experience and this idea of there not being a “there there” for the land that was here before and the people that we were. “There there” is also a reference to Oakland and trying to find a way to belong in Oakland as Native people. There are other ways that I tried to use it throughout the book that are subtler, but that was the basic idea that I wanted to dig into.

BTW: Does the city of Oakland have a large Native American community?

TO: The last time I saw numbers, there were 65,000 Native people in the Bay Area, but with any Native community it’s all relative because we’re a small population in this country for pretty awful reasons. All things considered, it’s a strong, vibrant community. To say large, or to say that it’s a big community, doesn’t feel true, though.

BTW: Have you always wanted to be a writer?

TO: I didn’t grow up a reader or a writer. I didn’t do well in school and wasn’t particularly encouraged to read. I was pretty good at sports. I played roller hockey on a national level from the age of 14 to 24 and I became a musician when I was 18. I earned a bachelor’s of science in sound arts and after I graduated, I got a job at a used bookstore, Gray Wolf Books, just outside of Oakland, and totally fell in love with reading and then writing. Then I felt like I was playing catch-up. I got pretty obsessive about it and tried to put in as much work as I could from there.

BTW: Who are some current Native American authors you admire?

TO: Terese Mailhot, author of Heart Berries [Counterpoint], which is now a New York Times bestseller, graduated from my same class at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and we sold our books within two weeks of each other. She and Layli Long Soldier, author of WHEREAS (Graywolf Press), which just won the National Book Award for Poetry, are the first two who come to mind who are really strong examples.