- Categories:

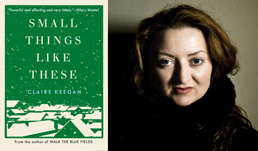

Claire Keegan on December Indie Next List Top Pick “Small Things Like These”

- By Emily Behnke

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These (Grove Press) as their top pick for the December Indie Next List.

“Claire Keegan works magic in this small novel about a truly good man in 1985 Ireland, and the difficult decision he faces at Christmastime,” said John Lynn of The Kennett Bookhouse in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania. “Keegan captures the extraordinary courage required to live an ordinary life with honor.”

Here, Keegan and BTW talk about her process.

Bookselling This Week: Where did the idea for Small Things Like These first come from?

Claire Keegan: I’m not sure stories come from ideas. The American writer Robert Olen Butler says fiction does not come from ideas, but from “the white-hot center of you, from the place where you dream.” It’s true that for some time I had been asking myself why we were so quiet and so afraid of speaking out in Catholic Ireland – and I like to think this book may address and attempt to answer or ask more questions about that question.

BTW: The story centers on a Magdalen laundry. What drew you to writing about this particular institution?

CK: I suppose the answer to the question of what drew me to writing about these institutions is already answered above, but this book is not set in the institutions and is the life story of Bill Furlong, a coal and timber merchant, a family man who works all hours perhaps not only to provide for his family but to keep what he feels at bay. It may well be the story of his breaking down, of his feelings and his past catching up on him – which coincides with where his work has led him. I see him as being unconsciously self-destructive.

BTW: Why did you decide to position this story from Bill’s perspective? And how did you craft his character?

CK: I wrote the story from Bill’s perspective because it is his story. And he was to some extent privy to what went on in people’s houses, was calling, and sometimes at odd hours, to the backs of people’s houses. It felt plausible for him to find what he found, to meet what he met. It seemed apt for the story to be told in his point of view – and then his past began to surface, which deepened my understanding of what he was finding, and how natural his finding it was. In Ireland, there’s a saying: “what’s for you won’t go past you,” an infuriating saying as it cannot be disproved – but I had a feeling that what happened at the end here was inevitable. I don’t believe there was anything else Furlong could have done.

BTW: Over the course of the story, Bill grapples with his own complicity regarding the abuse at the laundry, despite having just discovered it. His perception of the laundry is different from that of his wife, Eileen. Can you talk more about their viewpoints and where they diverge?

CK: I don’t know that their perceptions or understanding of what’s going on at the laundry do differ; it’s just that their responses differ. Eileen is in a difficult situation as she has five daughters to raise and is married to a soft-hearted man who gives away the change out of his pocket in a time when most, including the Furlongs, have little or nothing to spare. The poverty and unemployment of 1980s Ireland was devastating to so many – and Eileen’s response, which wasn’t uncommon, was to become deeply practical and to keep her husband in check, between the lines. They are living on the edge, and she knows it would be very easy to lose everything. Maybe she senses Furlong is on the slope. She doesn’t want anything to do with what’s going on at the convent. Neither, I think, does Furlong –- but the difference is he can’t help himself, can’t resist. You know, we are all inclined to do what’s easiest, what suits ourselves, and that’s character coming out.

Maybe the book is asking if affection and kindness were forms of weakness in this society. The writer John McGahern said that it was more acceptable to hit than it was to kiss someone in public in the Ireland he knew. I remember being with my father one day in the town of Tullow, waiting for my aunt to come down from Dublin on the bus, and when the bus did come, a young couple got off and walked up the street past the sweet shop, arm-in-arm. My father looked out at them and smiled and said, “isn’t it terrible to see a young woman like that and she blind.” There was the jeer, the backwardness. And I was my father’s sixth child so presumably he had put his hand on a woman himself more than once. But, of course, this doesn’t mean he ever showed affection.