An Indies Introduce New Voices Q&A With Jennifer Longo

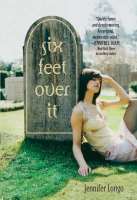

Jennifer Longo is the author of Six Feet Over It (Random House Books for Young Readers), a 2014 Summer/Fall Indies Introduce New Voices pick for young adults. A California native, Longo holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Acting from San Francisco State University and a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Theatre from Humboldt State University. After years of acting, playwriting, and working as a literary assistant and stints as an elementary school librarian and occasional storyteller, she decided to try her hand at prose. Longo currently lives with her husband and daughter on an island near Seattle.

Jennifer Longo is the author of Six Feet Over It (Random House Books for Young Readers), a 2014 Summer/Fall Indies Introduce New Voices pick for young adults. A California native, Longo holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Acting from San Francisco State University and a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Theatre from Humboldt State University. After years of acting, playwriting, and working as a literary assistant and stints as an elementary school librarian and occasional storyteller, she decided to try her hand at prose. Longo currently lives with her husband and daughter on an island near Seattle.

“Leigh’s father buys a cemetery, where she is expected to help families make choices. In her 15 short years, Leigh has suffered great heartache — parents who don’t seem to care or understand, almost losing her sister to cancer, and worst, losing a good friend with no chance to say goodbye,” said Valerie Koehler of Houston’s Blue Willow Bookshop. “Leigh’s acerbic wit gets all of us through this story and we cheer when she finally finds another friend to lean on.”

What was your inspiration for Six Feet Over It?

Jennifer Longo: When I was 12 years old, my parents bought our town cemetery, and the time I spent working and hanging out there presented more story ideas faster than I could ever put them down in one of the tons of notebooks I filled from the time I could hold a pen! The story I was interested in writing was one about a young person learning to let herself rely on other people when she’s been repeatedly taught not to all her life; having to teach this to yourself when you’re a kid is infinitely harder than having it modeled by parents or caregivers.

The cemetery felt like the perfect setting for both character and plot because it makes Leigh feel trapped and doomed. It is a confined place that is almost always viewed (by Americans anyway) as an ending, a desolate place of loss. What a challenge then, for this to be the place where Leigh blossoms — where she must strain not only against the confines of her own fear of death and guilt, but also against her fear of being physically trapped in the dark and dreary cemetery office, living in the graveyard separated from the “regular” world.

For Leigh, it feels like a punishment, like where she belongs. She isolates herself while outside her window flowers bloom and people love and are loved: they help one another and rely on each other, they mourn without being mocked, and she watches it all and wants so badly to figure out how to live that way. The cemetery breaks her heart and is her doom — and then ends up being her absolute joy and freedom. It is her destiny, as she suspects, but for a beautiful reason rather than the seemingly inevitable and sad reason she dreads.

Why do you think books that deal with death and dying are important for young adults?

JL: One of the things that gets me most about death — and I’m speaking specifically about America here — is that I truly believe no one knows anything about it at all. Unlike pretty much every other experience in life, we can’t gain more knowledge about death by growing older, having lots of life adventures, studying and practicing religion, going to school and majoring in Death 101 ... nothing will ever get anyone closer to knowing what happens after we die. It’s a complete mystery.

But mourning — how each of us mourns — is something a person can experience and learn about and understand. Everyone, no matter what age, develops his or her own mourning process. Of course, even then we don’t really understand how it works and we can’t control it. Adults often don’t get that. At all. They forget that kids need to learn. When a child experiences death, lots of adults seem drawn to micro-managing the child’s mourning. They attempt to guide the young person’s emotions, correct them at best, mock them at worst, as if there is a “right way” to be sad. Adults do this to one another all the time, but when it’s done to kids, it really pisses me off. Comfort is wonderful — telling a person how to be sad is insane.

This is where I think books about death directed at young people come in handy; very few adults understand how they themselves mourn, let alone have the capacity to comfort a kid without making the kid feel worse. Adults are often so eager to hand out their own version of what death is, what it means, what their religion dictates it is, and how loss must be dealt with. A book about a similar experience can maybe give a young person some breathing space if they’re getting a bunch of lectures and can help them feel less lonely, for there are far more similarities in our grief than there are differences. Perception matters, and kindness and confusion and anger are all normal and healthy when mourning. If a child has not experienced death, books about it can introduce thoughtful discourse and depict situations where kindness and empathy are paramount.

The main character in Six Feet Over It notes at one point, “Dying is such a grown-up thing to do.” That bit was lifted directly from my fifth-grade journal. A friend from school had died one summer, right on the heels of my teenage cousin. I watched the adults around me — teachers, parents, grandparents — argue with each other, getting all pissed at themselves and the kids for being too sad, not sad enough, all kinds of nonsense. I remember thinking, maybe the adults are freaking out because these little girls who died, they know something the adults don’t. Maybe it’s just reminding them that they have no idea what’s to become of us all and it’s scary for them.

When people are too sad to effectively help each other, books are good at stepping in. After that Summer of Death, I loved Lois Lowry’s A Summer to Die. I loved Katherine Patterson’s Bridge to Terabithia, and I reread them over and over. My parents called it “wallowing.” I called it “Trying not to fall into a dark pit of impossible sadness and confusion, so leave me alone I’m reading now.”

Books don’t judge. They’re there when you need them. Good ones can comfort and soothe and reaffirm that the reader isn’t insane. The reader is not alone. If any situation for young people calls for books, death has got to be in the top five, at least.

Are you a fan of Six Feet Under (the HBO series)?

JL: I love that show! A few people have asked, and some assume that my book is a reworking of the plot of Six Feet Under, but Six Feet Over It (a title my editor came up with) was written first in the form of a full-length play, years before Six Feet Under was ever on TV. And really, through journal entrie, while working in the graveyard, I wrote it 28 years before Six Feet Under premiered.

When I drafted the play in grad school in 1998, I didn’t have a TV and as I turned pages in each week in class and people read them, one of my friends kept saying, “Um, you really need to come over and see the commercials for this show HBO is doing. It’s all about death!”

I was so annoyed that I refused to watch Six Feet Under until the third season, and then I had to catch up and see them all because I loved it so much! Mostly for Nate and Brenda’s steamy make-out sessions. But, honestly, that show dealt with death and the American business of it in such an interesting way, a completely different way than that of my book. The two have about as much in common as Taxi, the TV show, and Taxi Driver, the movie.

You’re also a playwright. In what ways does each style of writing allow you to tackle themes and character growth differently? (And which do you prefer?)

JL: My agent and editor are constantly saying to me, “Yes, I understand what the story is about — now I need you to tell me what happens.” They are both intimately aware how my background in playwriting colors my novel writing. I just wanted to write a book about internal conflicts where people had a lot of long conversations with themselves and others in a graveyard. And sometimes weather was described. Which, in a play, is fantastic. But my agent and editor explained that book readers tend to enjoy a little something those in the publishing industry like to call a plot. Heh.

Which is not to say that plays don’t have plot, obviously they do, and some more external than others — but most often the conflict in a script is largely internal, revealed through emotion conveyed by dialogue. A play script like Patrick Meyers’s K2 is a perfect example: two guys are hanging off the side of the world’s second tallest mountain and are trying not to die … but what happens? Well … they kind of talk. A lot. And, sure, there’s some near misses with loose rocks and stressful climbing, but mostly there’s lot of holding on real tight. Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is an intricate portrait of a complex marriage, spanning decades of battles lost and won. But what actually happens on stage for two and a half hours (with intermission)? One couple hosts another couple for late night drinks and they play mind games while sitting on a sofa and occasionally exiting to a stairwell that leads offstage. Also drinks are stirred and refilled. And don’t even get me started on Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Allegory, shmallegory. I love theatre more than anything but that is three hours of two dudes waiting.

When I write prose, I feel most comfortable with characters revealed through dialogue, as play scripts are basically character studies in dialogue with a few choice stage directions (unless you are Shaw, in which case that ratio is sometimes flipped). Playwriting has made me fairly adept at figuring out what story I mean to tell, and how the characters will change as the story goes on, and I love story so much. But action matching the rising internal conflict is sometimes a mystery to me. And that’s where an editorial agent (Melisa Sarver White at Folio Literary, a genius at plot untangling) and a super-smart and patient editor (Chelsea Eberly at Random House, whose plot development skills are insane) help the book move from what it is about, into what happens to make that story reveal itself. I love writing plays, I love learning more about prose every day, and I will always write both.

What advice would you give a young adult interested in writing?

JL: Well, this will sound repetitive as there are some golden rules about this, but here goes:

Read. Read, read, read and think about why you’re drawn to the stories you’re drawn to. What’s the delicious thing about the stories those books/magazines/graphic novels/poetry/newspapers/blogs are telling you? Why do you love them, what is the thing about them you can’t get enough of, and how could you do that thing in your own unique way?

Write. Get into the habit of writing whenever the mood strikes you, and even when it doesn’t. Even if it’s just an idea. Never be without a pen and notebook — or even a phone to take notes on, whatever — and learn to set aside time devoted to writing. Journaling is a perfect way to develop ideas. Listen to people talking, eavesdrop, steal dialogue. Don’t read too many “how to write” books. Pick one or two good ones and don’t obsess. Those things can be great, but like parenting books, if you read too many you start running into conflicting advice and then you can get paralyzed with indecision. Glean the information that makes sense and is helpful to you, and then write and write and write some more. Find readers you can trust to be honest, whose opinions you actually care about, and who you will listen to without catering to, and who you can get ideas from. Then write some more.

What is your earliest memory related to reading?

JL: My parents let me order a book from the Scholastic book club, and I chose Russell Hoban’s A Bargain for Francis. It was this thin little paperback. I was seven years old and I still have it. My daughter reads it now. I hid in my room and read that thing a hundred times or more. I stared at the pictures and memorized every single detail. I loved the black and white and blue color. I loved the story and the outcome. I loved the tension and acting out the dialogue for each character. Oh my gosh. This is making me want to go read it right now. I loved that the characters were badgers and that was so funny to me, but seemed so normal. I loved that Francis wore a dress to school but hung around the house naked. I took really good care of it. The book is clean and intact despite the non-stop love I gave it. It’s one of the first things I would grab in a fire.

Are you working on anything now?

JL: The work-in-progress I’m revising for my editor is a novel about a ballerina in San Francisco who discovers, too late, that her body will never do what it needs to in order for her to become a professional dancer. Her entire life, it seems, has been moving toward the wrong end. And she kind of loses her compass and decides the best thing to do is go to Antarctica to winter over and find her True South, so to speak. I’m really, really motivated by setting. I love this story, and I hope it turns into something readers will as well. It’s been nice to get out of the graveyard and into Golden Gate Park and onto some ice.

If you were a bookseller, is there a book you would say all YA readers should read?

JL: If I was a bookseller and I was pushing one title, I would have to say E. Lockhart’s We Were Liars. That book blew my head clean off. Poetic prose, a story that unwinds slowly in the humid, summer ocean air, an amazing plot. I could die. It is so good.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three titles would you want to have with you?

JL: Three Desert Island Titles, my favorite game! I have a separate list for plays but I shall be good and stick to books here. And I’ll keep the entire Little House series (HarperCollins) out of it, as that is nine books but really that’s what I would bring if I could have unlimited titles. Oh, and Wendy McClure’s Wilder Life (Riverhead) as a companion piece. Okay, I’ll knock it off. Here goes:

-

Gift From the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh (Pantheon). I read it every year. I have given it as a gift more than any other book. Women, read this book to feel heard. Men, read this book to understand some ladies. LGBTQ, family, and friends, read this book for all that and to hear about a rad solo trip to the beach.

-

Time of Wonder by Robert McCloskey (Puffin). This picture book is not only beautiful but also depicts the childhood I desperately wish I’d had and feel like I must have in a past life. It is a gorgeous meditation on the seasons of life via the joy, discovery, and trials of growing up and slowly gaining independence on an island on the East Coast. And the parents are never around bugging the kids, the kids are outside all day, meeting new people, running around sailing boats and jumping off rocks with no adult supervision, falling and swimming and loving and respecting the world they live in and the people they are. Perfection.

- Wild by Cheryl Strayed (Vintage). Have you not read this? You need to go read this book right now. Then read everything Cheryl Strayed has ever written, starting with Dear Sugar, but first read Wild. When some people reach the end of their rope — when there’s not even a knot to hang onto — some people let go. Other people put a 70-pound pack on their backs and hike a thousand miles to figure shit out. Even if they’ve never hiked a step in their lives. Memoir is my favorite genre of literature to read, and this one is absolutely compelling and gorgeous, and don’t let Oprah’s love for it fool you, it is amazing. (That’s just a little Franzen joke, Oprah. I love you. And your chai tea. Call me.)

Six Feet Over It, by Jennifer Longo (Random House Books for Young Readers, Hardcover, 9780449818718) Publication Date: August 26, 2014.

Learn more about Jennifer Longo at taotejen.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As With Indies Introduce Debut Authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.