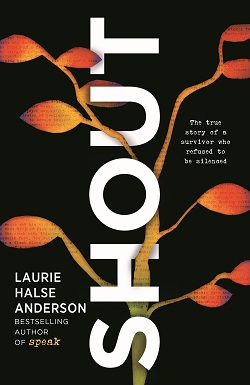

Laurie Halse Anderson on Spring Kids’ Indie Next List Top Pick “SHOUT”

- By Emily Behnke

Indie booksellers nationwide have chosen Laurie Halse Anderson’s SHOUT (Viking) as a top pick for the Spring 2019 Kids’ Indie Next List. Through free-verse poetry, Anderson offers both a call to action and a memoir, including her journey to becoming a writer, writing Speak, and what it’s like to meet with students in schools across the country.

“Laurie Halse Anderson invites readers not to speak but to shout in her new poetry memoir, a long-awaited follow-up to her bestselling YA novel Speak, which centers around a survivor of sexual assault,” said Mary Wahlmeier of Raven Book Store in Lawrence, Kansas. “In SHOUT, Anderson shares memories from her young adulthood when she herself was raped and how she found the strength to keep going. Between autobiographical poems lie fierce rants about rape culture and censorship, as well as love letters and encouragement to survivors of sexual assault. SHOUT is a fist raised to the sky, arriving on the heels of #MeToo and urging readers to never be silenced. A must-read.”

Here, Bookselling This Week talks with Anderson about the current conversation surrounding sexual assault in America.

Bookselling This Week: SHOUT is a memoir told through poetry. Did poetry allow you to access any parts of your memory or help you convey your memories in ways that prose could not? How so?

Laurie Halse Anderson: I think it helps me convey the memories. There’s a reason we have several different forms of textual narrative writing. I’m not going to speak for anybody else, but for my own purposes, my own writing, poetry allows me to get to the marrow of the story. I think poetry also creates moments where the reader can take a breath. You can read a poem and if it really connects with your heart, you want to pause. I think that the enjoyment of a book of poetry, for me at least, is the culmination of those deep experiences, and then the pauses. They build on each other and take it to the end, and then you close the book and you say, wow, okay, I felt that.

BTW: In “Cave Painting,” you share a little bit about your journey as a writer. What did that look like for you? What drew you to the world of books?

LHA: I was a little bit of a latecomer to the world of books. Although my mom would read to me all the time when I was little, I had a hard time learning how to read myself. I wasn’t one of those super wunderkinds who nailed it from the beginning. But once I finally understood I had some learning disabilities — and had some awesome public school teachers who helped me figure them out — I learned how to decode and I loved it. I can’t live without reading. It’s life. It’s breath. It’s water.

I always wrote for fun once I learned how to read, and I always wrote for self-expression. Writing poetry is what got me through my adolescent years. I think I might have had one or two poems published in the literary magazine in high school, but I was not writing for publication. I was writing for survival. And I had no intentions of being an author, ever. But you have to remember, when I was in high school, I wasn’t even thinking ahead to life. I was just trying to get through the days. As a working-class kid in college, I didn’t think of anything in the arts. I needed a job that would pay a wage. So, for most of the first 35 years of my life, writing was something fun on the side. Honestly, I think for me that was a great way to begin. I don’t have an MFA degree, so I gave myself permission to just feel the joy of creation and to try to figure out how to communicate more effectively, how to write stronger and better, but without any pressure.

BTW: In “Collective,” you address the fact that some young boys do not understand the trauma Melinda endures from her rape; specifically, they ask, “What’s the big deal?” You also close the poem with the phrase “a curiosity of boys.” Can you talk about what that means?

LHA: I just wrote an op-ed for Time magazine about what we haven’t taught our boys and how that damages everyone. I find with boys, no one talks to them other than to say “don’t get her pregnant,” because most parents out there still accept the myth that rapists are bad guys, they’re criminals. [They think:] “My son couldn’t be a rapist.” When, in fact, the overwhelming majority of sexual violence is committed by somebody that the victim knows, and often knows very, very well. This lack of discussion is because parents are uncomfortable talking about sex, because their parents were uncomfortable talking about sex. And so, you have boys who are hungry for information and it’s being withheld from them. If we treated teaching our children how to cross the road the way that we treat teaching our children about healthy sexuality, nobody would live to be seven years old.

Those are equally important things. You teach your kids how to cross the road safely, and you reinforce that conversation just like you reinforce the conversation you have with your preteens about road safety. You know, “Oh, look at that guy, he’s running a red light.” Just these quiet, consistent little things. A lot of really nice guys commit sexual violence. They’re nice in other aspects of their lives. They consider themselves to be nice people. They’ve tried to live their lives well. You really have to bring them down in conversations to get them to admit. Without knowing the impact that night had on his victim, he could do it again. It’s astonishing how little boys know about the impact of sexual violence.

Ninety percent of women who are victims of rape will develop symptoms of PTSD within two weeks of their attack. Twenty years later, 50 percent of those women will still be experiencing symptoms of PTSD. And let’s be clear, the victims of sexual violence are not just female — they’re also male, nonbinary, transgender, and genderqueer. We have a lot of really, really wounded people around. And we have the solution. The solution is to talk to all of our kids. The overwhelming percentage of perpetrators of sexual violence are male, and so we have to do a better job to do more to reach them.

BTW: Speak has been challenged in schools across America. In the wake of the #MeToo movement, what do you think the reaction to SHOUT will be?

LHA: We’re neck deep in the backlash to #MeToo, and we’re still seeing perpetrators of power being covered up by institutions that don’t want the reality that the guys who directed their movie or other powerful men have hurt women, have hurt people. When you bring these topics up, people are uncomfortable. And when people are uncomfortable, they yell at you. So, I think it’s going to be challenged. Bring it on.

BTW: In what ways do you think the conversations happening in schools about sexual assault are different today?

LHA: There’s a poem in SHOUT where I talk about a principal who pulled the fire alarm to get me to stop my presentation. That taught me that I had to alter my contract. After that experience, I started to include a clause in my contract where I say any discussion of Speak is going to include a discussion of human sexuality, and then I required the top administrator in the building to list which grade levels I’m allowed to talk to and to sign off on it. I’ve had schools look at that contract and say yeah, no thanks.

But it will be interesting for me to see how people like school administrators react to the book because we have seen some tremendous changes in 20 years. Just look at the growth of YA literature. Look at the growth of YA literature used in the classrooms. We’ve replaced that generation of older English teachers who still think that everybody needs to read the canon in order to be an educated human, and we’ve also replaced a generation of administrators. And so, I’m going to be hopeful and I’m going to say that there’s a lot of really interesting things going on in education. We have a lot of teachers and administrators who care deeply about kids and understand the power of literature. So, maybe it’ll be awesome.

BTW: What would you like to tell readers?

LHA: I’ve spoken thousands of times in the last 20 years about sexual violence and I’ve never visited a school, a library, a conference, or a bookstore where I haven’t had somebody come up to me afterward in tears. I get e-mails and letters and things like that daily, and not because I’m some big shot or anything. It’s because there are so many victims of sexual violence out there in the world, and we haven’t found the language to talk about this yet. That’s what I’ve been trying to do with my work — to help people find the words and to help people who haven’t been victims of sexual violence, so they don’t have to think, oh, how do I talk about this? How do I speak up? How do I shout? The other piece of this is learning how to listen with compassion and love and tenderness. That’s how we make the world better.

RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) is the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization. RAINN operates the National Sexual Assault Hotline (800-656-HOPE) and offers an online chat service.