- Categories:

A Q&A With David Nicholls, Author of December’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

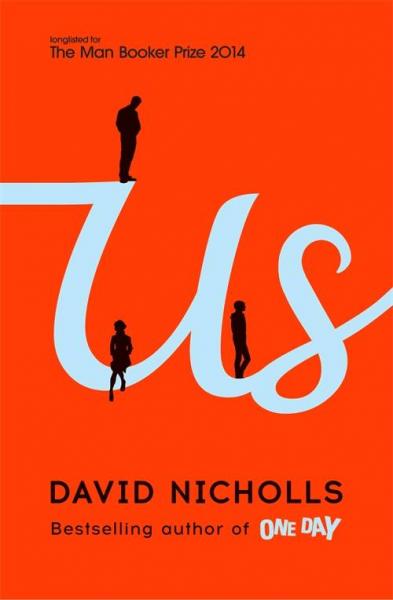

David Nicholls’ fourth novel, Us (HarperCollins), has been chosen by booksellers as the #1 Indie Next List Pick for December. Mary Cotton of Newtonville Books, in Newton, Massachusetts, described Us as a novel that “manages to be heart-wrenching and hilarious all at once.”

David Nicholls’ fourth novel, Us (HarperCollins), has been chosen by booksellers as the #1 Indie Next List Pick for December. Mary Cotton of Newtonville Books, in Newton, Massachusetts, described Us as a novel that “manages to be heart-wrenching and hilarious all at once.”

Longlisted for this year’s Man Booker Prize, Us combines Nicholls’ wit and poignant insight into strained family dynamics to tell the story of a middle-age biochemist, Douglas Petersen, who finds out in the novel’s opening pages that his marriage may have “run its course.” Details of Douglas’ relationship with his wife, Connie, emerge as the couple embarks on a “Grand Tour” of Europe with their son, Albie.

Nicholls’ last novel, One Day, was awarded the 2010 Galaxy Book of the Year Award. Nicholls is also a successful screenwriter for both film and television. In an interview with Bookselling This Week, Nicholls sheds light on many of his influences and preferences as a writer.

Bookselling This Week: Much of this novel is a balancing act: between comedy and semi-tragedy; between art and science; and between romantic and familial love. Why do you think it is important to include these conflicting — or, in some cases, congruent — ideas in one book?

David Nicholls: I suppose it’s that old need for conflict, for drama and friction. Tonally, the books and films I love constantly flip between comedy and pathos; Dickens at his best can make you laugh and cry, often within the same chapter. Salinger is a great comic writer, yet I’ve never read Franny and Zooey and not been moved. In film, Billy Wilder’s The Apartment is a brilliant comedy about loneliness, suicide, and despair. In other words, the best laughter, I think, is tinged with sadness and regret.

And in terms of the love story, contrast and conflict are vital. People rarely fall in love with their mirror image, and there’s no spark without friction. Look at Much Ado or Pride and Prejudice, Bringing Up Baby or When Harry Met Sally. In Us, Douglas and Connie have a wildly divergent view of the world, yet it’s this very difference that pulls them together, even if later it pushes them apart.

BTW: The book is split into 180 brief chapters. What effect do you think this episodic structure has on its readers?

DN: I’m fascinated by structure. A lot of novelists start with the blank page and improvise, but I like the scaffolding to be in place, and I like it to fit the story and themes. My last novel, One Day, had a very tight structure — 21 long chapters, each corresponding to the same day each year, and this provided the framework in which to have fun, improvise, play. Us leaps about through time and place. It’s about a journey, both literal and emotional, and so requires a much more fluid structure. We tend to remember long journeys as episodes, holiday snaps if you like; that terrible hotel, the missed train, the painting in the gallery, and I wanted a structure that reflected that experience and also propelled the reader onwards, so that they’re always thinking “just one more, just one more.”

Also, I was influenced by two wonderful novels, Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell, a portrait of a long marriage told through brief snapshots and anecdotes. Zadie Smith did something similar in her brilliant NW, too. And perhaps that structure owes something to my screenwriting experience; 180 story beats, each with a particular purpose, each leading inevitably on to the next.

BTW: The Petersens are on a “Grand Tour” of Europe while deliberating the fate of their marriage. What is the significance of an epic backdrop setting the scene for a microcosmic-by-comparison issue concerning one family?

DN: One of the mottos for this book was, “There’s no such thing as an ordinary marriage.” Even the most placid and stable of relationships has its secrets and passions and tragedies. The trick, I suppose, is how do you write a small, self-contained world without the novel feeling small and self-contained. Us was written after a prolonged period of travel through Europe promoting One Day, and I loved the idea of these domestic tensions playing out against these great cities — petty irritation in the Louvre Palace, unspoken resentment in the Van Gogh museum — that contrast between the grand and the everyday.

BTW: There are many great novelists who depict modern family dynamics in a unique way. Are there any writers on this topic, in particular, who have been an inspiration to you? How do you hope your book stands out among others in its genre?

DN: So many, and many of them are from the USA. I love Lorrie Moore, Jennifer Offill, and Anne Tyler, all of whom are razor-sharp on family, love, and marriage. Writers like Eugenides and Franzen manage to give family dynamics an epic scale that recalls the 19th century social novel, and I admire that too. John Cheever, Richard Yates, Updike, Roth, Maxwell, Salinger: their books were a huge influence on me and are something to aspire to in the way they give “ordinary” lives a real scale and drama. I’ve already mentioned the Bridge books of Evan S. Connell — massively underrated, I think — but if I could pick one particular writer as an influence on Us it would be Cheever, and the way he portrays ordinary, sometimes rather dull and conservative men whose rather conventional behavior disguises huge emotions; lives that are poised to go off the rails, for better or worse.

BTW: Independent booksellers — British and American alike — have clearly embraced your work. In her Indie Next List nomination, Mary Cotton named Us “a brilliant and humanizing picture of mature love.” What role has the support of independent booksellers had on your career?

DN: Well thank you, Mary. I’m very grateful to her and to all independent booksellers. Like libraries, bookshops were an essential part of my education while I was growing up, and I still feel that a town without a bookshop has something missing. In the 1990s, they also provided me with a livelihood. For many years I worked for a bookshop in Notting Hill, where I ran the children’s section with a rod of iron (and once sold a book of poetry to Julia Roberts, though I don’t think that experience had anything to do with the movie). There’s nothing like working in a bookshop to bring home the importance of the staff’s enthusiasm and expertise. So, yes, I’m hugely grateful.