- Categories:

Spotlight on ABA History: “More Than Merchants: Seventy-Five Years of the ABA”

- By Emily Behnke

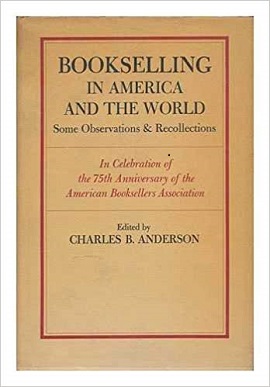

Bookselling This Week’s new occasional series, “Spotlight on ABA History,” features excerpts from Bookselling in America and the World, an anthology edited by Charles B. Anderson, as well as pertinent summaries from the anthology.

Published in 1975 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the founding of the American Booksellers Association, Bookselling in America and the World features four main articles that discuss all aspects of the bookselling world as it existed from 1900 to 1975.

Editor Charles B. Anderson served as president of the ABA Board of Directors from 1958 to 1960 and was the owner of Andersons bookstore in Larchmont, New York.

Here, readers can enjoy another excerpt from the chapter “More Than Merchants: Seventy-Five Years of the ABA,” written by Chandler B. Grannis, the editor-in-chief of Publishers Weekly from 1968 to 1971.

This chapter discusses ABA’s operations during World War I and its move to a full-time staff, among other topics. It also discusses issues of pricing policies and agreements made between publishers and booksellers during the early years of the ABA, which are currently illegal under legislation such as the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Robinson-Patman Act.

Booksellers can read an earlier excerpt from this chapter here.

___

World War I and the Early Twenties

The book trade, like all the nation, were caught up in World War I. Sympathy for the Allies ran high, and war books were selling briskly. The crusading element of America’s short, decisive part in the war was reflected sharply in the 1918 convention rhetoric of President Macauley [Ward Macauley of Macauley Bros. in Detroit, Michigan]. He voiced the vast majority’s consensus when he called the war “a conflict of ideals, democracy versus autocracy.”

A new burst of energy marked the ABA’s immediate postwar years. In 1919 the ABA’s speakers included a veteran among publishers, Major George Haven Putnam; one of the younger breed of publishers, B.W. Huebsch; and a young newspaper critic, Heywood Broun. Topics included postwar business opportunities, direct selling, and library sales.

In 1920, postwar super-patriotism was calmly viewed in an International YMCA executive’s talk on “Building Americanization Through Books”; he reminded listeners that “we are all immigrants.” Meanwhile, ABA President Charles F. Butler demanded “fewer titles and better distribution,” a dual goal almost as difficult to achieve as the deathless “fewer and better books.”

Plans and programs continued to bubble, and at the 1921 convention in Atlantic City (PW gave 60 pages to the full proceedings!) Frederick G. Melcher, managing editor of PW, announced a plan for a “Year-Round Bookselling Campaign.” This incorporated the new Children’s Book Week, but included also a promotion theme, with slogans and promotion materials, for each month in the year. But operating problems were not ignored: President Eugene L. Herr of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, acclaiming the 33 1/3 percent discount that had been secured from publishers “in recent years,” said ABA studies had now “clearly shown that 36 percent was indispensable to the successful conduct of a retail business,” And so, for several years, the ABA’s battle cry in dealing with publishers was to be “One-third plus 5.” The arithmetic was interesting; the idea was entirely clear.

In its first year, May 1921 to May 1922, the Year-’Round Bookselling Campaign was a center of attention. Sent out in this effort were “1,507,784 posters, circulars, circular letters and personal letters” to booksellers, librarians, churches, clubs, schools, magazines, newspapers and individuals. Meanwhile, experiments were being made with the bookmobile idea, and ABA secretary Belle Walker reported on the value of a “Book Caravan” to rural areas.

The ABA Goes Full-Time

All through the early 1920s, the need for a full-time staff executive with a broad program was becoming apparent. Under the prodding and enthusiasm of the energetic ABA President Walter V. McKee of Sheehan’s, Detroit, the 1924 convention voted to create the post of executive secretary, and the board hired, to fill it, a young promotion man from Western Union, Ellis W. Meyers. He took on the job in time for the 1925 convention, and vigorously began lining up a program based on Mr. McKee’s theme, “More and Better Bookselling” — a constructive switch on the old cliché. My Meyers launched an “ABA Page” in PW, running several times a month on the average, with the magazine’s cooperation. At the same time he resumed the publication of the monthly ABA Bulletin.

A big decision at the 25th annual celebration was to establish a Cooperative Clearing House to which booksellers sent their orders for New York publishers. At the Clearing House, these orders were consolidated for shipment to the stores, thus saving substantial carriage costs. This service lasted until President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 reduced the parcel post rate for books to a 1 1/2 cents a pound, making the Clearing House unnecessary. An associated service, the Consolidated Warehouse (called American Booksellers Service Co.) was also set up and maintained until 1946. But one idea endorsed strongly in 1925 was never carried out — a proposal for a telegraph delivery service for books.

As Mr. Meyers described it in 1926, the kind of service given by the Clearing House illustrates the vast difference in scale between the industry of the 1920s and that of the 1970s. Each morning, New York publishers would pick up orders that booksellers had mailed to the Clearing House; packages in fulfillment of these orders would go to the Clearing House that same afternoon. The Clearing House staff would then “enclose” each retailer’s order from the different publishers’ packages, and ship the books to the dealer in a single case of 100 to 150 pounds. (A 150-pound lb. case cost less than half the freight charge of five 35-lb. packages, Mr. Meyer said.) Shipment could be made the day after the receipt from publishers, or two or three days’ orders could be accumulated. Delivery in those days of complete railway service was prompt.

Cooperation with other organizations (on matters other than net price) had assumed a permanent place in ABA affairs by the mid-1920s. At the St. Louis convention in 1926, publisher Ben Huebsch reported on the latest bookseller education program held in cooperation with the College of the City of New York, the Booksellers’ League of New York, and the Women’s National Book Association[1]. (Pittsburgh booksellers held a course the following March, with 50 students.) Carl Milam, executive secretary of the American Library Association, cited the booksellers’ mutual interest with the ALA in the latter’s “Reading with a Purpose” promotion. The publishers, now organized, since 1920, in the National Association of Book Publishers, presented their joint promotion plans. “Books in Motion” was the slogan reported this time by the highly capable and resourceful NAPB executive secretary Marion Humble, a handsome lady whose romantic profile graced the PW convention reports each year in a different portrait.

Among 22 resolutions passed by the ABA in 1926, one was to incorporate the Association — partly to avoid personal liability in any legal judgments against the organization.

This was a convention at which the varied nature and different problems of booksellers in different fields were recognized by the holding of eight round table sessions. They were for college stores[2]; religious stores; departments or shops; large city stores; also for the consideration of bookstore accounting and finance; and of advertising, mail order and “special efforts.”

The Book Club Battle Begins

As this historical sketch is prepared, the book clubs have been a fact of book distribution for almost 50 years. But shortly after ABA’s 25th anniversary, they were brand new — and frightening. For several ensuing decades the clubs were primarily regarded by many leading booksellers as simply elaborate cut-rate mail-order schemes, unredeemed by their massive promotion of many titles. For at least a quarter-century, the ABA fought them, through litigation and attempted competition, and still, in principle, opposes their price-cutting aspects. At the 1927 convention, Cedric R. Crowell of the Doubleday stores, argued that, while the Book-of-the-Month Club would stimulate the sale of particular titles, it would hurt the sale of books generally; that the literary guild policy of taking subscriptions through bookstores would injure normal store operations; and that the bookstores could offer better service than the clubs.

As a counter-move, the ABA tried in 1928 an elaborate “Bookselection Plan” under which the Association would obtain selected books from publishers at 55%, supply them to dealers at discounts of 40% to 43%, and send the difference on operating the plan and advertising the selections. The plan did not catch on — not enough, anyway, to sell the budgeted 10,000 books per three-month period. This despite a presumably savvy selection committee: booksellers Joseph A. Margolies and Marion Todd, reviewer-editor Harry Hansen, authors Inez Havnes Irwin and Will Durant. Mainly because of the plan, the ABA by 1930 had a $17,500 deficit which it paid off by selling $25 debentures to booksellers; debenture holders waived their interest and most of the bonds were redeemed at a discount.

Promoting Promotion by Booksellers

Other ABA energies, fortunately, went into the encouragement of booksellers’ own promotion. R.G. Montgomery of J.K. Gills, Seattle, in 1927 told about “Making the Radio Sell Books for You,” and Franklin Spier spoke on advertising, showing layouts of cooperative ads. The ABA made available to its members a series of ad mats featuring seasonal and gift themes. Their success was noted at the 1928 convention, when President John G. Kidd was also setting approval for a cooperative national ad campaign “to sell the bookshopping habit.”

This was an expansive era for books; rental libraries were more and more popular, books were appearing as drugstore merchandise and selling by mail was increasing.

Along with these serious matters, and a full round of convention reports, how-to talks and special-interest round tables, the conventions of the ’20s had their frisky moments. PW reported them faithfully (if not, perhaps, completely) under what became for a time an annual heading, “Playtime at the Convention”; play was apparently stimulated by Prohibition. The 1927 sessions at New York’s Hotel Commodore were enlivened by a carnival night from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m., and climaxed by a banquet where 1,000 guests heard — among other celebrities — Will Durant, Bruce Barton, Henry Seidel Canby, and a repeated ABA performer and friend, Christopher Morley. The precedent for today’s celebrity parades at conventions was established.

__

Watch upcoming issues of Bookselling This Week for more from Bookselling in America and the World.

[1] The League, formed in 1895, was an active local trade association in its early years, later mostly a social group; renamed, 1972, Book League of New York. The WNBA was formed November 13, 1917, in the Sunwise Turn bookshop, N.Y.C., as the Women’s National Association of the Booksellers and Publishers.

[2] Already, following informal talks at ABA meetings, bookstores in this field had formed in 1923 the College Bookstore Association, later the National Association of College Stores.