- Categories:

Ci6 Keynote Speaker Temple Grandin on Teaching Kids to Think Like an Inventor [4]

- By Liz Button [5]

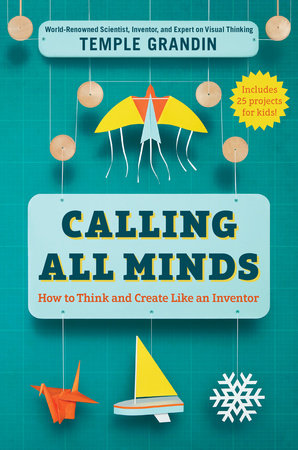

Temple Grandin — scientist, inventor, engineer, autism spokesperson, and author of the children’s book Calling All Minds: How to Think and Create Like an Inventor [6] (Philomel) — gave a lively keynote speech at the sixth annual ABC Children’s Institute [7] in New Orleans.

Grandin is a professor of animal science at Colorado State University and has written many books on autism, including Thinking in Pictures (Vintage), Animals in Translation (Scribner), and Animals Make Us Human (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). In 2006, HBO made an Emmy Award-winning movie about her life, and in 2016, she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Her new book for children, Calling All Minds, includes personal stories, facts about classic inventions, profiles of famous inventors, and copies of patents, as well as more than 20 of her personal childhood experiments, such as making a kaleidoscope, constructing a kite, and fashioning a pair of stilts, all of which come with clear instructions so that kids can recreate them. The book also delves into the scientific questions behind the inventions while teaching children the value of tinkering, fiddling, and being curious.

“One of the things that got me interested in doing this book is that we’ve got to get kids out doing a lot more hands-on things, the kinds of hands-on things that I did as a child,” Grandin told booksellers at the Thursday, June 21, keynote. “A lot of the projects in the book are projects I actually did as a child. We’ve got a lot of kids today who are growing up not using tools.”

One of these, Grandin said, is a recreation of the fifth-grade woodworking project she completed as the second girl in her elementary school to be allowed to take the class. The hands-on activities in this book, she said, teach kids the tinkering skills they need to create new inventions all on their own.

“Duplicating my childhood projects, especially my aviation projects, was not all that easy because I couldn’t get exactly the same materials, so kids are going to have to tinker with this to get it to work — I spent hours tinkering with this,” she said.

When meeting elementary school kids at her speaking events, Grandin told booksellers, she is often horrified to find out that many have never made a paper airplane. When she teaches college students in her livestock handling classes, she is surprised to learn how many of them don’t know how to use a compass or are more used to drawing on a computer than on paper.

“We need to get kids out doing real things,” said Grandin. “A lot of college students today have never used a ruler — they didn’t even know what a compass was. I’m also really concerned in this country that we’re losing know-how in skilled trades. I do a lot of work with the food industry and I’ve worked with all kinds of skilled tradespeople that would have been in special ed today: dyslexic, kind of quirky and weird, maybe autistic.”

There are many negative consequences when hands-on learning is not seen as essential, she said; for example, people no longer know how to make or use some of the food processing equipment of the past. Fortunately, said Grandin, some states are now starting to put more value on trades and including them in school curriculums once again.

“I get asked all the time how I got interested in the cattle industry, and I tell them I was exposed to it as a teenager,” said Grandin. “You’ve got to expose kids to enough different kinds of careers to get them interested. We should keep teaching theater in schools— that can turn into a good career; also, the skilled trades, like theater, are not going to get replaced by computers.”

It’s also important to get kids doing jobs outside of the home, like dog walking or delivering newspapers, she said.

“Learning how to work is really important,” said Grandin. “The problem I see today is kids are not learning how to work. Academic skills and work skills are not the same skills. I’m seeing smart kids get straight As and then they do really badly in the workplace. They haven’t learned work skills.”

Many talented children are also getting labeled early on in their school careers, said Grandin, which cuts off many future avenues to them. Kids, she said, need to be guided in developing their strengths so that they get recognized for what they are good at.

“I’m seeing too many kids getting these labels and I’m worried about our educational system screening them out,” she said. “A lot of minds that are really brilliant have really uneven skills. You can be brilliant at some things and atrocious at others. In education, we have too much emphasis on the things they’re atrocious at and not enough on building up the talent area.”

There are many kinds of thinkers out there, Grandin said, including photo-realistic visual thinkers, as she is; pattern thinkers, who are good at math and music but may have trouble reading; kids with verbal facts minds, who can recount facts about their favorite subjects; and auditory thinkers, who are great talkers. In Grandin’s case, while she was never good at algebra or math as a child, as a visual thinker, she had no trouble with geometry.

There are many kinds of thinkers out there, Grandin said, including photo-realistic visual thinkers, as she is; pattern thinkers, who are good at math and music but may have trouble reading; kids with verbal facts minds, who can recount facts about their favorite subjects; and auditory thinkers, who are great talkers. In Grandin’s case, while she was never good at algebra or math as a child, as a visual thinker, she had no trouble with geometry.

“Everything I think about is in pictures. And we need us visual thinkers,” said Grandin. “Visual thinking, artificial intelligence, and computers and people with autism, ADHD, and dyslexia are all ‘bottom-up’ thinkers. You form the concept from specific examples. We’ve got to get these kids out doing a lot of stuff because you’ve got to fill up the database. That’s exactly how my mind works.”

In fact, Grandin concluded, many famous innovators, like Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Albert Einstein, and Steve Jobs, would likely have been diagnosed as on the autism spectrum in today’s educational system.