- Categories:

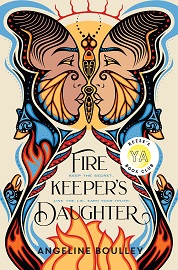

Angeline Boulley on Spring Kids’ Indie Next List Top Pick “Firekeeper’s Daughter” [4]

- By Emily Behnke [5]

Indie booksellers across the country have chosen Firekeeper’s Daughter [6] by Angeline Boulley (Henry Holt and Co. Books for Young Readers) as one of their top picks for the Spring 2021 Kids’ Indie Next List [7].

After putting her dreams on hold to care for her mother, 18-year-old Daunis witnesses a shocking murder that thrusts her into the heart of a criminal investigation. But as the investigation gets closer and closer to home, she must decide how far she’s willing to go to protect her community.

“This debut grabbed me from the start and kept me totally immersed in the story of a strong, self-described nerdy young female struggling with the normal problems of belonging, with the added element of being half Native American,” said Carol Putnam of Skylark Bookshop [8] in Columbia, Missouri. “This novel offers a rich combination of a young person’s struggle with identity plus the unique challenges of being associated with a tribe and the problems of meth use and addiction. Add in a pulse-pounding mystery on top of it, and you have a true page-turner.”

Boulley is an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and storyteller who writes about her Ojibwe community in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. She is a former director of the Office of Indian Education at the U.S. Department of Education. She lives in southwest Michigan, but her home will always be on Sugar Island. Firekeeper’s Daughter is her debut novel.

Here, Bookselling This Week talks craft with Boulley.

Bookselling This Week: Where did the idea for this book come from?

Angeline Boulley: The idea came when I was a senior in high school. My friend at a different school told me about a new guy she thought I’d be interested in. I kept asking about him until she told me he didn’t play sports and hung out with the stoners. I played four different sports in high school, so he was definitely not my type after all. At the end of the year, there was a huge drug bust and it turned out that the new guy had been an undercover officer. I remembered thinking what if we’d met and had liked each other? Or . . . what if it wasn’t that he liked me, but that he needed my help? Why would an undercover investigation need the help of an ordinary Ojibwe girl?

BTW: Can you tell me about your experience writing it? What was your process like, and how did you feel?

AB: When my daughter was a pre-teen I decided to write the Indigenous Nancy Drew story that had been in my thoughts since I was 18 years old. I’d wake up early to write for a few hours before going to work. Waiting for my son at hockey practice or during my business trips, I’d use any free time to write plot details or character insights. I had no idea what I was doing when I started, but I kept at it. I read a lot of YA to learn more about pacing, dialogue, and plot beats. Sometimes I’d need to set the story aside because, well, life. But the ideas would keep coming and finally I’d be compelled to start another draft. This process took 10 years.

BTW: This story is centered on Daunis Fontaine, a young girl working to understand her biracial identity, her role in her Ojibwe community, and the direction she wants her life to take. How did you craft her character?

AB: She started out a lot like me. We both have an Ojibwe dad and non-Native mom. We’re both light-skinned and have felt, at times, that we were “not enough” because we didn’t live on the reservation. But over the 10 years of writing and revising the story, Daunis became her own person. Very different from me in how we process things. She’s much better in math and science than I am. She knows her language better than I do. Sometimes I’d try writing her with rougher edges, but it felt like an outfit that was the wrong size. Her decisions would feel independent of me, but perfect for her.

BTW: One thing that struck me while reading was the way Daunis anticipates the needs of not only her mom, but her community as well. What drew you to this aspect of her personality?

AB: Daunis has some formative experiences early on where she learns to compartmentalize her identity and code switch. Those hurtful experiences cause her to develop the ability to read situations and protect herself accordingly. That skill, paying attention to how people behave, leads Daunis to recognize other peoples’ needs — especially those she cares about.

BTW: This book focuses on Ojibwe culture, language, and experiences, but it’s also a page-turning thriller that takes some dark turns. What was it like blending these two ideas together?

AB: I had to answer the question, was I writing a thriller with an Ojibwe coming-of-age angle or was I writing an Ojibwe coming-of-age dressed up like a thriller? It was the latter. Once I knew that the core of the story was about Daunis claiming her identity and place in her community, it helped me to see the thriller plot beats as a means to an end.

BTW: I was also struck by the way joy was embedded into this book. Daunis survives and reckons with a number of traumas, but they’re bolstered by a sense of support, of community. Can you talk more about that?

AB: My mantra while writing was that I was writing about trauma but I wasn’t writing a tragedy. There is so much joy in my community, and I really wanted to show that.

BTW: Can you talk about the role independent bookstores play in your life?

AB: I used to travel a lot in my former career. What I loved most was exploring new locations and seeking independent bookstores. I’d find the spot where my book would be shelved someday, making space in the universe for it!