- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Ava Reid [2]

- By Emily Behnke [3]

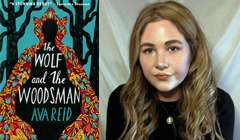

Ava Reid is the debut author of The Wolf and the Woodsman (Harper Voyager) a Summer/Fall 2021 Indies Introduce [4] adult selection.

Ava Reid is the debut author of The Wolf and the Woodsman (Harper Voyager) a Summer/Fall 2021 Indies Introduce [4] adult selection.

After being surrendered by her fellow villagers as a blood sacrifice for their king, Évike, the only woman in her pagan village without powers, survives a monster attack that slaughters all but one of her captors, the disgraced prince Gáspár. Together, they must stop Gáspár’s cruelly zealous brother from seizing the throne. They have no one to rely on but each other, but trust can easily turn to betrayal, and as Évike discovers her own hidden magic and connects with her estrange father, they must decide whose side they’re really on.

Reid grew up in Hoboken, New Jersey, and currently lives in Palo Alto, California. She earned a degree in political science at Barnard College, where she focused in religion and ethnonationalism.

Indies Introduce panelist Olivia Edmunds-Diez of Boulder Book Store [5] in Boulder, Colorado said of Reid’s book, “I was deeply impressed with this fantasy novel and its connections with Hungarian and Jewish mythology and folklore. This book is dark, magical, and haunting as the characters face villains that are both fantastical and human. I could not put this down, and raced to the ending to learn what would happen next!”

Here, Edmunds-Diez and Reid discuss the folklore and fairy tales that inspired the author’s book and the parallels she draws to the real world.

Olivia Edmunds-Diez: What inspired you to write The Wolf and the Woodsman?

Ava Reid: It really was an amalgam of a lot of different things. The first was that I read an anecdote about Saint Stephen, the first Christian king of Hungary, who had his nephew and heir apparent’s eyes stabbed out because he was a pagan and he did not want a pagan to inherit the throne. The symbolic resonance of that image, the breathless brutality of it, immediately conjured a bleak, violent world where zealousness and cruelty made monsters of men.

Most fantasy books take for granted the homogeneity of their countries, and that every character will feel an unconscious, unbending sense of patriotism toward their “homeland.” I wanted to problematize that a little bit. I wanted to show that creating the identity of a country is an inherently violent process that involves the exclusion – and sometimes the utter destruction – of anything that doesn’t fit the aspirational nation-state. Throughout history Jews have been subject to precisely that kind of exclusion and prejudicial treatment. And of course, if you want to write a fantasy book with Jewish characters, you can’t write about that sort of unconscious, unbending patriotism. How do you love a country that doesn’t love you back? What are you willing to give up in order to belong? Those became the central questions of The Wolf and the Woodsman.

OED: Your novel opens with a matriarchal village filled with magic. Why was it important for you to begin your story this way?

AR: The Wolf and the Woodsman is a story about exclusion. I wanted to show all the ways that Évike has been told, again and again, that she doesn’t belong in the place she calls home. She doesn’t have magic, and therefore she’s alienated from all the things that are supposed to comprise her identity – even (perhaps especially) her gender. Évike goes between two rigidly gendered worlds, from the matriarchy of her home village to the patriarchy of the larger kingdom, and she doesn’t really fit neatly into either of them. I did this very intentionally: during her and Gáspár’s initial journey through the outlands, they barely encounter any men; once they reach the capital, Évike virtually never interacts with a woman. The strict gender roles in The Wolf and the Woodsman were another way for me to show that Évike is perpetually unmoored and excluded – and, I would argue, Gáspár as well. They’re both characters who fail to perform gender the way they’re supposed to. It’s another identity that is denied to them.

OED: What parallels do you see between your novel and the real world?

AR: I was very aware of the contemporary political resonance this book would have while writing. The topic of Hungarian folklore is deeply politicized – as is the case with all European folklore, to a greater or lesser extent. The pagan revival movement in Hungary is overwhelmingly ethnic nationalist, right-wing, and antisemitic. And I’ve gotten a lot of blowback from Hungarians who think that I don’t have the right to delve into this folklore because I’m Jewish, much the way Évike is excluded from the stories that are told in her pagan home village.

I think issues of ethnic nationalism, religion, and identity will always be relevant – and I think they’re especially relevant in contemporary politics. The question of who gets to belong “authentically” to a certain nation or culture is something that’s constantly up for debate. The power of folklore and fairy tales is nothing to scoff at. These sorts of cultural touchstones are so squabbled over because they confer legitimacy upon whoever “owns” the narrative. For example: the turul is one of Hungary’s national symbols. It’s used on the coat of arms of the Hungarian Defense Force and is commemorated as a statue outside of Buda Palace. But it’s also one of the symbols associated with the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian Nazi party. In The Wolf and the Woodsman, the turul confers power (both actual and symbolic) upon whoever possesses it, and virtually every political faction is fighting over it. That fight is very much going on in the real world, too.

OED: The beasts and otherworldly creatures were frequently terrifying! How did you create such monsters?

AR: As Évike notes in the book, the only magical creatures that have managed to survive the purging of the kingdom are those that are able to use deception to hide their true forms. I wanted the folklore and fairy tales in this world to be surreptitiously dangerous because, in a meta sense, they are. There’s an ugly underbelly to virtually every single European fairy tale you can think of – think the antisemitism in Rumpelstiltskin.

Most of the creatures they encounter are based off “real” creatures from folklore. I get a lot of questions about the chicken monsters, which are loosely inspired by a creature called a lidérc. It’s taken many forms across the map of folklore – some versions have it as a creature like a mara, or a vampire, some kind of sleep paralysis demon. One Hungarian version says it hatches from the egg of a black hen. I thought that was pretty uniquely creepy, so I decided to use it.

In addition to the lidérc, the witch (Hungarian: boszorkány) they encounter as well as the seductive forest sprite (Hungarian: vadleány) both have ravenous appetites. The motif of consumption is one that’s really interesting to me and comes up a lot in the book. I see it as sort of the ultimate form of control, of power, whether it’s Vilmötten swallowing the star or (spoilers) the king eating the eyes of the turul. So I wanted all the monsters they encounter to reflect that motif.

OED: What's next for you? Do you see Évike's story continuing?

AR: The Wolf and the Woodsman is definitely a standalone—I wanted it to have the brevity and neatness of a fairy tale. But I do have a second book, coming summer 2022, that is technically set in the same world (though displaced in time period and location). It’s a proper fairy tale retelling of Grimm’s “The Juniper Tree,” set in an analogue for Victorian-era Ukraine. Whereas The Wolf and the Woodsman is for fans of Naomi Novik and Katherine Arden, this book is more in the tradition of Angela Carter and Catherynne Valente. It’s darker, sharper, and stranger, with Gothic sensibilities. I’m really looking forward to sharing it.

The Wolf and the Woodsman by Ava Reid (Harper Voyager, 9780062973122, Hardcover Fiction, $27.99) On Sale Date: 6/8/21

Find out more about the author at avasreid.com [6].

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors [7] in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do [8].