- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Shannon Pufahl [4]

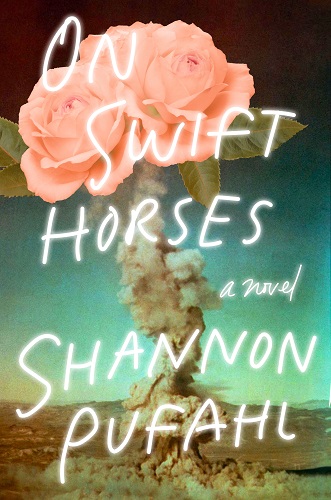

Shannon Pufahl is the author of On Swift Horses, a Summer/Fall 2019 Indies Introduce [5] adult debut and a November 2019 Indie Next List [6] pick.

Pufahl grew up in Kansas and received her master’s in English from the University of Kansas. She currently teaches fiction, creative nonfiction, and writing across genres at Stanford University and is a PhD candidate in American Literature at the University of California, Davis. She lives with her wife and dog in the San Francisco Bay area.

Pufahl grew up in Kansas and received her master’s in English from the University of Kansas. She currently teaches fiction, creative nonfiction, and writing across genres at Stanford University and is a PhD candidate in American Literature at the University of California, Davis. She lives with her wife and dog in the San Francisco Bay area.

Anne Holman of The King’s English Bookshop [7] in Salt Lake City, Utah, served on the panel that selected Pufahl’s book for the Indies Introduce program.

Said Holman, “It’s the late 1950s. The Korean War is over, and Vietnam is getting started. For brothers Julius and Lee, newly home on leave, getting out of Kansas and starting anew in San Diego means the beginning of the American Dream. For Lee, it’s his new wife, Muriel, and the promise of a house in the suburbs. For Julius, it’s less clear. These were still early days in the West; folks were watching atomic bombs blow up from the tops of hotels on Fremont Street in Las Vegas, and decency laws still lived on the books and in people’s minds. As we follow Julius and Muriel, we see two people who are part of the Greatest Generation trying to be true to themselves.”

Here, Holman and Pufahl discuss the time period and landscapes in which the author places her characters.

Anne Holman: There are so many things to talk about in this novel, which is why it will be a favorite hand-sell for booksellers. You’ve spoken about your close relationship with your grandmother. Can you tell us a little more about that and how it figures into this novel?

Shannon Pufahl: My grandmother was a Catholic girl from rural Kansas who made a small fortune selling used cars. She was wry and funny, she loved to gamble, and she didn’t suffer fools. I spent much of my adolescence in cars and casinos, with my mom and grandma, in the western landscapes that would come to define my aesthetic and eventually prompt me to move out of Kansas. It is the great privilege of my life to have been raised by her and my mother. Both of them taught me the value of risk, how to play cards and gamble, and how to walk through the world like I belonged in it.

My grandmother died the year I started this novel, and I understood from the beginning that I would be writing a kind of homage to her — if not to her actual life, then to her spirit. Muriel is very much inspired by my grandmother, who found so many ways to be herself without models or language, and in a time before it was acceptable or fashionable for women to be as powerful as she was.

AH: While this is definitely a novel of the western United States, do you think it could have worked as well somewhere else? Why or why not?

SP: From the beginning, I wanted to borrow the Western form and remake it. I was curious about what might happen if the heroes of that kind of American story were a woman and a gay man, and the settings urban and suburban. How might the conventions of the Western accommodate those things? What can be accomplished inside the Western form, what remade, and what critiqued?

Also, the landscapes of the West and the Great Plains, which are so bound up in our American imaginary, seemed absolutely necessary for the kind of dreaming done by the characters — dreams of success, discovery, and connection. Our great national story is, in essential ways, about the movement west toward the sea, through the imposing landscapes of the mountains and the arid plains. The literal physical procession through these landscapes is central to our mythologies.

Yet, much of the book is about progress and risk, and the relationship between them, and in that way almost any American moment or place will do. From the beginning of European exploration and exploitation, those two ideologies — progress and risk — are the beating heart of nation-formation. But for the novel, I specifically wanted California and Nevada at mid-century, because those places and that moment converge beautifully and terribly: atomic testing in the deserts of Nevada, the displacements caused by the new interstate system, the housing boom, the postwar prosperity that enabled massive defense spending and the space race. The beginning of the kind of imperialism we see in Korea and the proxy wars that follow, the migration of millions of Americans from rural places to cities in the north and west. The social movements that will both liberate and mire us follow from this confluence, nowhere more present and powerful than in the American West in 1956-57. The characters in this book can glimpse, from this vantage point, futures previously impossible to imagine.

Yet there’s an irony at the center of this historical moment, one that I hope comes through in the novel. The great forces of commerce and technological progress in the 1950s enabled many liberations in the following decades, yet they also deepened inequality overall. We are living in the apotheosis of this irony.

AH: Horses play different roles in On Swift Horses, both literally and figuratively. Were you a horse lover as a young girl and can you elaborate on why they are central to this story?

SP: I loved the track very early in my life and demanded that my 16th birthday party be held at the Woodlands in Kansas City, where my mother and grandmother placed bets for me. Horseracing felt like everything I loved about gambling, all together. The excitement of the track is undeniable and much more communal than sitting at a card table or a slot machine in a casino. In most games of chance, all values are abstracted — an ace is worth this, a cherry this, etc. But horseracing is very literal and visceral.

My parents also had an old nag named Bonita, who lived quietly among the cows and the barn cats in our southern field. I think Bonita was, in many ways, the model for the horse Julius brings back from Nevada. Horses are not as central to farm life in Kansas as they are in, say, Texas, so having a horse was somewhat unusual, and Bonita was alternately doted on and ignored. My father’s cousin, who lived up the road, had appaloosas, and I spent some time around them, learning to ride and about their care. There was not much to learn about either from Bonita, who was old and grumpy, and very independent. When my dumb uncles tried to ride her, she would run them into low-hanging branches and under eaves. But I did learn that horses are singular creatures and, of course, central to any mythology of the American West, whether in native or vaquero culture, or later in the cowboy culture of the late 19th century. They symbolize a certain kind of freedom, the way the automobile would come to symbolize something similar at mid-century. Both allowed human mobility and speed on a scale previously unimaginable.

AH: Why did you decide to set the novel at the close of the Korean War?

SP: The Korean War is not much written about in fiction. It is very often eclipsed by the wars that preceded and followed it: WWII and Vietnam especially, the former considered heroic and the latter folly. Yet Korea was very much the early theater of the Cold War and a product of American bravado following the victories of WWII. Many of the conflicts that shape the second half of the 20th century are instigated and informed by Korea, and we are still living with its legacy.

My grandfather was a veteran of the Korean War and I was also curious about what that must have been like for him. Like my grandfather, both Lee and Julius come out of the Navy and into a time of great prosperity, but it would have been very difficult for them to understand exactly what their service meant. Korea, like so many wars that will follow, was a conflict without a definitive end. The war was sold to Americans as a struggle for democracy and freedom, but these abstractions were not always satisfying to those who served, who saw what things really looked like on the ground. Korea really sets the stage for the 1960s and that decade’s powerful critique of war and oppression.

AH: The conflicting pressures of gender, class, sexuality, and social expectations define much of your characters’ narrative arcs, but also help illustrate often-overlooked aspects of the period in which the novel takes place. Can you elaborate on the inspiration for these arcs and how you researched them and worked them into the story?

SP: As a writer, I was very interested in how people like Muriel and Julius, who are working-class people from rural isolation (like my own family), would have learned to articulate their desires in a time before “identity” as we now understand that term. They would have had very little access to diversity, to the urban spaces that allowed identity movements to thrive, and virtually no language about themselves to draw on. The only talk about homosexuality they would have heard, in any public space, would come through McCarthyism and the public hunt for the “lavender menace,” which conflated homosexuality with communism and anti-Americanism. I wanted to see how language, how the form of the novel itself, could accommodate this dearth. I wanted to document that moment in history when a community was just beginning to form, and depict the historical and political milieu that enabled it.

There are some very good histories of this era — and about queer life in particular — and many point to the late 1950s as the moment the revolutions of the ’60s and ’70s truly began. Many forces enabled those revolutions, and I hope the novel illuminates some of them, especially since many people still think of the 1950s as halcyon, prosperous, and without the political impact ascribed to later decades. I have not read many stories about queer people set in this time, and certainly very few that take a historical, 21st-century view of the era. Those stories that do exist are largely about wealthy, white urbanites, whose privilege allowed them a measure of safety and invisibility. Raids, imprisonment, beatings, death — all were common, especially for poor men and people of color. It might surprise many to learn that queerness, which is now central to our public discourse about civil rights, was only 50 years ago punished sadistically and yet very rarely spoken of. Of course, this is still the case in many places, in the U.S. and around the world. But to me, sexuality is the central risk in a story about gambling generally, and the characters’ considerable bravery was a guiding light for me.

On Swift Horses by Shannon Pufahl (Riverhead Books, 9780525538110, Hardcover Fiction, $27) On Sale Date: 11/5/2019.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors [3] in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do [8].