- Categories:

A Q&A With Ottessa Moshfegh, Author of July’s #1 Indie Next List Pick [3]

- By Liz Button [4]

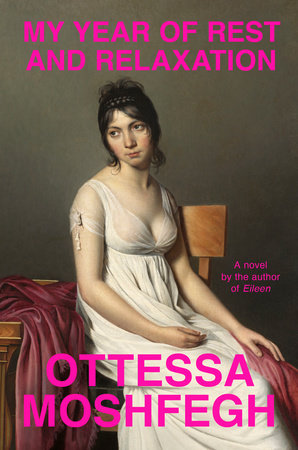

Booksellers have named My Year of Rest and Relaxation: A Novel [5] by Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin Press) as their number-one pick for the July Indie Next List [6].

Set in pre-9/11 New York City, the novel is narrated by a woman in her mid-20s who seems to have it all: she is model-thin and pretty, has a degree from Columbia, a job at a fancy art gallery, and a large inheritance. However, both her parents are dead; she’s isolated aside from visits from her college friend Reva, who, though obsequious, is jealous and resentful; and she can’t seem to leave her manipulative, on-again, off-again finance bro boyfriend.

Set in pre-9/11 New York City, the novel is narrated by a woman in her mid-20s who seems to have it all: she is model-thin and pretty, has a degree from Columbia, a job at a fancy art gallery, and a large inheritance. However, both her parents are dead; she’s isolated aside from visits from her college friend Reva, who, though obsequious, is jealous and resentful; and she can’t seem to leave her manipulative, on-again, off-again finance bro boyfriend.

To escape this psychic pain, Moshfegh’s protagonist resolves to sleep for one whole year, aided by an extremely irresponsible psychiatrist prescribing an alphabetical array of pills. Her objective is to wake up refreshed, rested, and cured of her alienation from everyone and everything, but as one might guess, things don’t play out as planned.

“At first, My Year of Rest and Relaxation feels like the end of something, like a novel about the end of someone’s life. But Moshfegh has a way of affirming life unlike any other author,” said Gregory Day of BookPeople [7] in Austin, Texas. “Repercussions of grief, emotional exhaustion, and the general anchors of life hurl a young woman into the warm embrace of the idea of hibernating for a year. Of course, this cannot be so simply done. In true Moshfegh fashion, this journey is brimming with laconic humor, her brand of ne’er-do-wells, and ample substance intake, which all lead to one of the most existentially satisfying reads in recent memory.”

Moshfegh is the author of the novella McGlue (Fence Press), which won the Believer Book Award, and the short story collection Homesick for Another World (Penguin Press). Her first novel, Eileen (Penguin Press), was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Man Booker Prize and won the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction. Moshfegh’s fiction has been published in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, and Granta, and has won numerous awards, including a Pushcart Prize and the Plimpton Discovery Prize.

Moshfegh is the author of the novella McGlue (Fence Press), which won the Believer Book Award, and the short story collection Homesick for Another World (Penguin Press). Her first novel, Eileen (Penguin Press), was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Man Booker Prize and won the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction. Moshfegh’s fiction has been published in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, and Granta, and has won numerous awards, including a Pushcart Prize and the Plimpton Discovery Prize.

Here, Bookselling This Week speaks with Moshfegh about her novel of alienation.

Bookselling This Week: Where did the idea for this book come from?

Ottessa Moshfegh: It came from having lived in New York before 9/11 and then after, and it came from spending a lot of time on the Upper East Side, which is where I was when I started writing the book.

I was a senior in college. The short story is that I have a cousin who had worked in one of the Twin Towers, and because it was impossible to reach anybody — I couldn’t even call my mother, none of the phones were working that day — I didn’t know she had survived until the next morning. So I spent September 11 in this state of negotiating with God, but it wasn’t even a negotiation, it was like, oh, ok, I see what’s going on: if my cousin is dead, it really means that life is just an absurdly cruel joke and I’m in hell and there is no point. But if she was alive, I would give it another shot and try to have some optimism. And then she made it, so [I felt like] now I have to do something. That was a long time ago, but that was my experience. What I ended up doing was having an existential crisis. I think everybody did.

BTW: When you were writing this book, how were you able to get into the headspace of your protagonist and channel her dark, nihilistic, complex thought process?

OM: I thought about the character, about what her experiences have been that would lead her to have certain opinions and attitudes, what her inherent personality is, and then about where the book needs to go. But a lot of the writing is just letting the voice direct itself into narrative and storytelling. [My protagonist] was a character that felt close to me. She isn’t the kind of person I knew when I was her age but her interiority felt, in a way, easy to access because she was so vulnerable.

Whereas Reva is more difficult to understand. She’s actually a more complicated character. She has different levels of self: she has the self that she has in her private world, she has the self that she has with her family, with her friends, at work; the self that is interested in self-help and therapy, the self when she is walking down the street and having to look a certain way. But the protagonist just exists in the totality of her mission; she doesn’t have a life, basically.

BTW: Some readers have called your book an existentialist novel. Would you agree with that?

OM: I wouldn’t disagree. I think that it’s a far cry from [Jean-Paul Sartre’s] No Exit, but it certainly shares its central theme, which is people trapped in their own minds. What I wanted to say about this book, though, is it that it has a sense of humor; it’s trying not to take itself too seriously — it’s not trying to feed existential philosophy through fiction. I think it’s the only thing that I could have written about. It’s the biggest question that I have, and I also think that it’s a ridiculous question to ask and one that we’re going to continue to ask. I think I couldn’t survive seeking an answer without having a sense of humor and I think it comes through in the book, the absurdity and that it’s funny.

BTW: Did you do any research on the interactions between and the quantities of all the different pills the protagonist was taking to see if her intake would actually be survivable?

OM: There’s a fantastical aspect to the novel, which you find when the medicine I made up, called Infermiterol, comes up. Also, Dr. Tuttle [the psychiatrist] isn’t a completely real character either, so I’m sort of employing this creative liberty, which is an awesome thing that you get to do when you’re writing fiction. I’m stretching the boundary of what we know in the real world. If you read this novel with no sense of humor, you’d be like, oh, she never could have survived all those pills. And then it’s like, ok, well then, the book is over. But it’s like the audacity of thinking that she could and what would happen is why the book exists. So I didn’t need to research those things because that was not a realist part of the book.

BTW: In response to the question “Which book by someone else do you wish you had written?” in the New York Times’ “By the Book” column, author Lauren Groff named you [8] among several authors she admires, saying she envies your “ironic snappiness.” Same question.

OM: I really admire Michael Ondaatje. I admire Nabokov. I admire Edith Wharton. I don’t read a lot of my contemporaries; if my friend writes a book I’ll read it, but I don’t read a lot of fiction. I read mostly nonfiction and I’m probably more in awe of nonfiction writers who can synthesize gross amounts of information and make arguments. It just feels like such a gift to have access to those books. I don’t know if I could do it myself. I might want to control it too much that it would end up being fictional. I’m not a journalist. A huge part of being a fiction writer is having power to create the world, so if I had to just describe the world, I think I would get really frustrated.

BTW: What are you working on now?

OM: I’m doing research right now for my next book, which is really fun. I’m reading about Victorian America and California, in particular San Francisco. I’m reading about Chinese history and opium, and I’m reading about the history of prostitution in the United States, immigration — all kinds of stuff. I’m just following the breadcrumbs for this next novel that is going to be, I think, something of a ghost story. So I’m excited.

BTW: What have your experiences been like at indie bookstores, both as a patron and an author?

OM: In L.A., I live several blocks from Skylight Books [9], which is a great bookstore. When I’m in New York, I tend to go to McNally Jackson [10] or the Strand [11], and when I’m in Boston, there’s a really good bookstore in my hometown, which is a suburb of Boston, called Newtonville Books [12]. And those are the ones I know the best. I think the difference between going into an indie bookstore and going into a Barnes & Noble is like the difference between going out to dinner with the love of your life versus going on a blind date with someone you met on OkCupid. At indie bookstores there’s so much more human thought put into the way books are arranged and presented.