- Categories:

Elizabeth J. Church on The Atomic Weight of Love, May’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

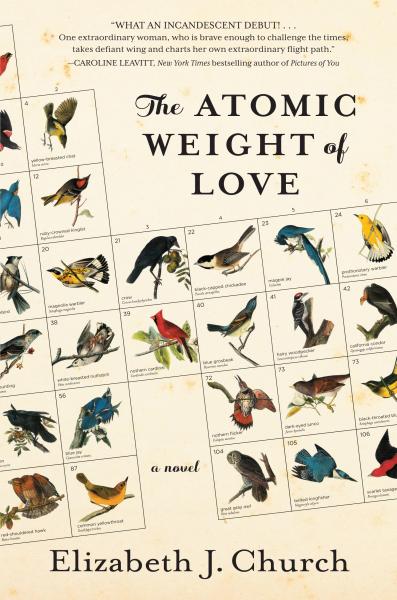

Booksellers have selected The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church (Algonquin Books) as the number-one Indie Next List pick for May.

In her debut novel, Church writes about the life of Meridian Wallace, a young ornithologist who falls for the older but brilliant physicist Alden Whetstone. At the cusp of World War II, Meri follows Alden to Los Alamos, New Mexico, leaving her academic pursuits behind to support her husband as he commences work on the Manhattan Project. In the decades that follow, Meri realizes just how much she’s given up and begins to redefine and reclaim herself.

“Filled with sharp, poignant prose, this novel mimics the birds Meri studies, following her as she struggles to find her wings, let go, and take flight. Church gives readers a thoughtful and thought-provoking examination of the sacrifices women make in life and the courage needed for them to soar on their own,” said Anderson McKean of Page & Palette in Fairhope, Alabama.

Bookselling This Week: The Atomic Weight of Love gives readers insight into the unique world of Los Alamos, New Mexico, in the 1940s, where scientists from around the country were brought for the launch of the Manhattan Project. What inspired you to write about this particular time and place?

Bookselling This Week: The Atomic Weight of Love gives readers insight into the unique world of Los Alamos, New Mexico, in the 1940s, where scientists from around the country were brought for the launch of the Manhattan Project. What inspired you to write about this particular time and place?

Elizabeth J. Church: I grew up in Los Alamos, the daughter of a research chemist (who worked on the Manhattan Project) and a biologist, my mother. I was inspired by the women I grew up knowing — my mother’s generation, the women who married the bomb scientists. These women were often brilliant in their own right and had moved to the isolation of Los Alamos to support their husbands’ careers, more often than not at the expense of their own careers and academic ambitions. They instead devoted their energies and substantial talents to raising their children, and I was one of the Los Alamos children who benefited from the efforts of these gifted women. They were my neighbors (a Ph.D. mathematician to whom I was often sent by my mother for help with my math); my teachers; my Brownie and Girl Scout leaders; my music teachers; and the mothers of my childhood friends (one would patiently dictate long division problems for me and my friend when we ran to her house after school to enjoy — yes, it’s true — more mathematical challenges). I wanted to honor these women and to contemplate what they could have been and done, had they been able to partake of the hard-won fruits of the women’s movement, of the evolution of the boundaries and expectations of male-female relationships.

BTW: Meridian sacrifices quite a bit, most significantly her academic career, in order to live up to the expectations of a traditional housewife. Did the women of Los Alamos make more sacrifices than their counterparts in that era, or were their experiences the norm?

EJC: This is a good, if tricky, question to answer. I think the answer lies in how women of the time defined their expectations. For example, what hopes had they fostered as girls, and what had they been told were the limits of their horizons? I suspect that the women of Los Alamos expected, through their educations, to stretch their minds and learn. Did they also expect, in the end, to succumb to the “Mrs. Degree” so prevalent in the time’s college campus culture?

I certainly think that all women of that era sacrificed on many levels. But, too, I suspect that many considered raising children to be the highest calling, a most laudable endeavor. I think for Meridian, the conflict comes because her expectation was to have a Ph.D., to pursue her academic interests on a professional, as opposed to “make-do,” level. She recognized early on that she was not likely to become a mother — she did not play with dolls. Her expectations were thwarted, and thus her sacrifice. She was caught in changing times, and she was an outlier — not permitted to be a true participant in men’s scientific discussions and gritting her teeth through seemingly endless conversations between women about child-rearing adventures. Meridian’s experience may have been more the “norm” in Los Alamos, simply because of those women’s educational attainments, their exposure to other, more varied options than single-minded motherhood, and her expectations.

BTW: Why did you select ornithology, specifically the study of crows, to be Meridian’s primary academic passion?

EJC: The book is in part a love song to the mountains of northern New Mexico, and I wanted for Meridian to be outdoors, in a splendid natural setting. Bird behavior got me where I wanted to go — whereas other biological disciplines might not have so readily met my creative needs. I have a personal, long-standing interest in birds in particular (more their behavior than precise identification), and I have an abiding fascination with the intelligence of crows. I’d already read widely about crow intelligence, and I thought that someone of Meridian’s intelligence would find the bird of particular interest — they were a good match. I also felt that crows perfectly mirrored the outstanding intellect that attracted Meridian to Alden. Finally, I’ve known many people who are afraid of crows, who either buy into the disparaging mythology surrounding the species or who have a natural antipathy toward them. I wanted to change minds, to spread the word about crows and their intelligence, and to pique readers’ interest by gently teaching.

BTW: While following Meri from decade to decade, readers watch her take small steps toward becoming an independent, sure individual. Why did you choose to write about a woman undergoing this transformation from meek to powerful?

EJC: Many who know me might well argue that I achieved my own evolution from meek (well, somewhat meek) to powerful (well, somewhat powerful) through the law. Through the law, I learned better ways to argue, more effective ways to fight and challenge — despite being a female (when I entered the law in 1983, it was still largely a very male profession — women tended to practice only the very “female” discipline of family law). So, in a way, I was writing about my own progression, my own growth. But I think the overarching reason I chose to write about this particular transformation is my rock-hard commitment to women’s need to not only find their voices but also to be wholly confident in using their voices and to shout, if need be. I have lived through a time where a woman who asserted herself was a “bitch,” and I well recall talking with friends, trying to come up with a parallel word for men who stood up for themselves (there wasn’t one, of course). I well recognize that things have changed for women, but I also believe we’re not done yet — not as long as election rhetoric can include the kind of completely disparaging and dismissive language as this election has held, and not as long as pay discrepancies remain (in April 2016, women are still earning less than 80 cents for every dollar men earn). I think we can all — mothers, daughters, and the men who love us — benefit from watching Meridian change and grow. We can remind ourselves to continue to challenge the confining cultural stereotypes and to dismiss all that would narrow our horizons.

BTW: Did the process of writing The Atomic Weight of Love inspire you to reflect on any aspects of your own life, or were there any elements of the story inspired by your own experiences?

EJC: To some degree, I’ve already answered this wonderful question, but there is one large area that I’ve not yet touched upon, and that is my relationship with my mother. Meridian spans the gap between my mother and me; she creates a bridge of understanding that I did not have before I wrote the novel. My mother and I went to war early on, and we were two very strong, opinionated, stubborn, and energetic rivals. She had her World War; I had the disaster that was Vietnam. She had a childhood of enormous financial deprivation (the Depression), and I had idyllic Los Alamos — at least until my father died, depriving us of the income and “inner circle” status we’d had as members of the national laboratory’s community. My mother had presidents she could admire; I had Watergate. She had strict sexual mores, and I had the sexual revolution and free love. She had cocktail hours (which she, for the most part, shunned), and I had the psychedelic experience. By taking Meridian’s viewpoint, living in her time and with her influences, I came to a better understanding of what had formed my mother’s character and political stances. She and I had reached a peace — at long last — prior to when I began writing the novel, but writing the novel cemented that peace and increased our understanding of each other. She expressed great admiration (along with fear for me) when I quit the law and began writing. She was afraid for the financial risks I was taking, but she admired what she called my “spirit.” I am sorry she did not live to see this and that I cannot share this with her — both the novel itself (although she would have hated parts of it), and the novel’s near-miraculous reception.

BTW: How does it feel to have your debut selected as the #1 Indie Next List Pick for May, as chosen by indie booksellers from around the country? Are there any independent bookstores you’re particularly excited to visit while on your book tour?

EJC: I keep waiting for all of this to become REAL. I never dreamt of this sort of open-hearted, generous reception for my book, and I am hugely honored. I cannot imagine a story that will ever be as close to my heart as this one is, and for it to find such an enthusiastic audience surpasses every expectation I could have fostered. The independent booksellers mean the most to me — their unadulterated love for the written word, their respect for writers. These are the people who truly understand what “labor of love” means, and this book has been a 58-plus-year labor of love. I’m thrilled to see ALL of the independent bookstores and adamantly refuse to choose one or two or three or four above the others. I wish I could go to them all — to meet and thank the people who keep alive the sensory experience of the printed word. I am in their debt — as both a reader and a writer.