- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Belinda Huijuan Tang

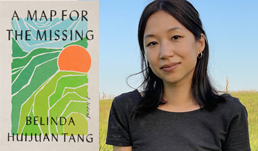

Belinda Huijuan Tang is the author of A Map for the Missing, a Summer/Fall 2022 Indies Introduce adult selection, and August 2022 Indie Next List pick.

Belinda Huijuan Tang is the author of A Map for the Missing, a Summer/Fall 2022 Indies Introduce adult selection, and August 2022 Indie Next List pick.

Tang is from San Jose, California and currently lives in Los Angeles. A Map for the Missing is her debut novel. She was a Truman Capote Fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and before that, she lived in Beijing and studied at Peking University. Her writing has received the Michener-Copernicus Award and a Bread Loaf Work-Study Scholarship.

Jhoanna Belfer of Bel Canto Books in Long Beach, California, served on the panel that selected Tang’s debut for Indies Introduce. Belfer said of the book, “In Belinda Huijuan Tang’s novel A Map for the Missing, an urgent overseas phone call alerts university professor Tang Yitian that his estranged father is missing, forcing Yitian to return to his family’s rural village in China and confront the past he’s worked so hard to leave behind. A gripping debut from an author to watch!”

Here, Tang and Belfer discuss A Map for the Missing.

Jhoanna Belfer: A Map for the Missing weaves together two compelling mysteries: the disappearance of an estranged father in 1990s rural China and the conflict 15 years earlier that ruptured the family’s ancestral ties to one another and their village. How did your own experiences influence or inform these two storylines?

Belinda Huijuan Tang: The story was influenced by my family’s own. My father grew up in rural China. The summer before he was supposed to leave the village for college, his grandfather, who’d largely raised him, disappeared. That summer, my father rode trains around the province looking for him, but he was never found. This story stuck with me from childhood onwards. I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

I think my mind snagged on it because of how little closure my father must have had. Disappearance is different from a death, because the act of disappearing itself feels outside of the natural course of life. It leaves you with very little to make a story out of, and the burden becomes on those who are left to make meaning out of what has happened.

JB: Familial duty and personal ambition play central roles in the novel, as characters like Tang Yitian and Tian Hanwen wrestle with their own desires versus their families’ and society's expectations. How does the context of China’s Cultural Revolution complicate these individual struggles?

BHT: I grew up in an environment where I was lucky enough to consider personal narrative and ambition whenever I made choices for my life. The Cultural Revolution made it so that an entire country’s decision sets were limited, and most people couldn’t believe in dreams in any individual sense. That didn’t mean people didn’t have dreams, rather, that for most people that dream was amputated before the point that it could be ‘chased,’ as we might call it. Yitian and Hanwen are both characters with ambitions for college who know those ambitions won’t be fulfilled in various ways: Yitian, because the gaokao (the college entrance exam) has been de-commissioned for a decade; Hanwen, because she’s caught up in the rustification program that relocated city youth into the countryside.

JB: Reconnecting with Tian Hanwen, Yitian’s former study partner and first love, offers him a glimpse into what life could have been like if Yitian had stayed in China. Why was it important to you to include her storyline?

BHT: Yitian has had a difficult life, but in many ways when we meet him in the beginning of the novel, is living a life close to what he would have dreamed for himself. Hanwen’s story was important to me as an example of someone whose life has closed in around her. As a result, she’s had to completely revise the person she thought she would be. The gaokao represented the major way ‘out’ at the time, so when she can’t pass the exam, her choices become much more limited. Because she’s a woman, the set of options presented to her are even more narrowly defined and center around marriage.

Most of the people who came of age during the Cultural Revolution weren’t as lucky as Yitian, and I didn’t want the book to only tell his story. I didn’t want the book to say, oh, if you’re smart and work hard then you can overcome the effects the Cultural Revolution and gendered expectations, because that wasn’t true.

JB: You lived in Beijing from 2016 to 2018 while working on early drafts of the novel. How did your lived experiences of China as an adult compare to stories you’d heard from your family growing up?

BHT: Growing up, my family often went to China during summer vacations, so I knew that the country had changed a lot from the stories I’d heard when I was a kid. Every place changes over the course of decades, but China is particularly fascinating to me because of the speed of that change. When my parents left China, the country was 25% urban and now most of the population lives in cities. During our summer visits, whenever we went a few years without visiting, Hefei (the nearest large city to my family’s hometown) would become unrecognizable to me. I always thought it must be so taxing on people who live there, keeping up with such constant flux and churn.

I was always particularly fascinated by village life because it was so far away from what I’d known. The village was the center of my father’s life, but, like many villages across the country, our village now is largely empty. All the young people have moved away into the cities, because that’s where the opportunities are. The only people who are left are the elderly and small children whose parents send them to be raised by their grandparents. The world I tried to capture in this book doesn’t exist anymore, and Yitian is seeing the beginnings of that disappearance when he returns home.

When my parents immigrated to the US in 1988, they thought America was rich, America had skyscrapers, America had the newest technology. Now China is just as much those things. That was another thing I wanted to explore — this feeling that the place you’ve left is actually growing towards the place you’ve immigrated to.

JB: The novel opens with Yitian’s conflicted journey from Stanford to “home” in rural China so he can lead the search for his missing elderly father. As he readies for the trip, he questions his sense of belonging in either place. Do you feel that Yitian’s outsider status is specific to him or reflective of the larger immigrant experience?

BHT: I was trying to capture the sense of loss that is part of immigrating, and the way that home becomes a place of the mind that doesn’t have a container in reality. The place you hold in your mind of home is fixed; meanwhile, that place is shifting all the time and can’t serve as a real place of belonging any longer. It is fascinating to me that so many people immigrate knowing that this loss is going to happen. That’s an agreement they make.

When I was living in Beijing, I had the sense that America, the place that was my home, was over time getting farther away from my reach. Things were shifting politically and culturally so much, and when you’re not physically present in a place, you feel like a spectator rather than someone who these changes are happening to. Something similar is happening to your personal relationships, on a more micro level. I wondered how that feeling might accumulate over a course of years and decades, how it might leave a residue of alienation.

A Map for the Missing by Belinda Huijuan Tang (Penguin Press, 9780593300664, Hardcover Fiction, $27) On Sale Date: 8/9/2022

Find out more about the author at belindahuijuantang.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.