- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A with Sara Daniele Rivera

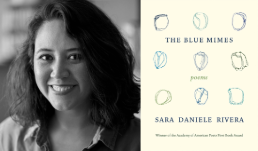

Sara Daniele Rivera is the author of The Blue Mimes, a Winter/Spring 2024 Indies Introduce poetry selection.

Rivera is a Cuban/Peruvian artist, writer, translator, and educator from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her poetry and fiction have been published in literary journals and anthologies and use both speculative and realist lenses to explore themes of grief, migration, memory, and the liminal spaces between language and silence. Her drawings, sculptures, and installations focus on text-in-space as social intervention and draw on practices of communal storytelling to bring moments of curiosity and tenderness to public art. She often develops projects through community-based collaborations. She translates between Spanish and English, focusing primarily on Peruvian poetry. She lives in Albuquerque with her husband, cats, and turtles.

Devon Overley of Loganberry Books, Shaker Heights, Ohio, served on the panel that selected this title for Indies Introduce.

“The Blue Mimes explores political and social upheaval in the United States, while also focusing on the individual experience of navigating such events, both presently and in our memories," said Overley. "Sara Daniele Rivera intertwines English and Spanish to present a collection of poetry that is deeply personal, while remaining recognizable to those in the public at large who have also lived through these experiences.”

Here, Rivera and Overley discuss The Blue Mimes.

Devon Overley: This collection covers recent events, but also gets rather intimate, addressing things like body image, eating disorders, and various kinds of loss. Is there an underlying theme that you feel unifies all the poems?

Sara Daniele Rivera: I think of loss, absence, and searching/questioning as unifying themes in the book. The chasms carved out by personal and collective grief, but also gaps in understanding, in identity or a sense of belonging — the loss that comes when we feel distant even from ourselves.

In the poem that deals with my eating disorder, “With a Destructive Obsession,” I tried to capture the feeling of erosion, the desire I had to carve away at my body and exist in a limited, liminal space. The smaller I became, the greater the internal absence grew. I felt detached from a body that would never be enough. There are many ways we lose our selves, gulfs that form between our minds and our bodies, and those forms of loss can be incredibly intimate and difficult to repair.

DO: What do you want people to understand about you and your life through your poems?

SDR: I’m always less interested in what readers take away about me and more interested in what they bring to the poems themselves or come to understand about themselves if the poems happen to connect with them. I hope the book finds the readers it’s meant for, people who might be able to process their own experiences or grief through it.

Of course, there are parts of my life laid out plainly in the book, and I hope what shines through most is the deep love I’ve experienced in my life, even in grief. This is an elegiac book, in which I mourn so many people I’ve lost. I wrote to capture the textures and shades and private languages of beloved relationships, with my grandparents, my friends, and of course with my dad. I hope the book is one of the spaces where their stories live on. For me, their love is the source of hope within grief, the thing that keeps tragedy from winning out in the end.

DO: How do you feel society has helped or hurt those who deal with similar issues of grief and perseverance without guaranteed positive outcomes?

SDR: This is such a difficult question to answer in a societal moment when our country is actively funding a genocide in Gaza. When mass shootings and racial violence are part of our daily reality. You want to believe that there is a moral line, a scale of human loss and suffering that should be unconscionable, but that isn’t always the case. Political and capitalistic and individualistic interests take precedence over the loss of life, over the basic human empathy that should move us to say, enough, no person should have to endure this loss.

And yet, at the same time, I find constant hope in the way communities uplift one another. The networks we create between activists, friends, families, and neighbors to offer witness and care. Every day I see people I love working to create a better future and fight against oppressive, systemic injustice. I see the moments in my hometown when people come together to eat menudo and raise funds for a family struggling to afford funeral costs. I see poets putting together vigil events and protests, advocates working in policy and nonprofit spaces so that everyone in our state can have their needs met. Society often fails us in our grief — so it’s all the more important for us to invest in each other, in the people and places we belong to.

DO: You include sketches alongside and sometimes within your poems. Did you draw them? In what ways do you feel that they amplify your words?

SDR: The book contains line drawings of mine (the seeds on the cover that reappear in one of the poems, and the drawing of the door in the final section break) as well as drawings of my dad’s in the first two section breaks. I’m a visual artist as well as a writer; text and visuality often come together across my creative practice.

It always felt important to me that the book contain these visual elements, though I didn’t really know why until I was deep in the process of putting the book together. I figured it out by the time I was writing the acknowledgments. My dad is the one who taught me to draw, and his drawings always had a sketched style, a kinetic, unfinished feeling. When I went through a phase of drawing intensely photorealistic portraits in high school, he encouraged me to loosen the line, to allow my drawings to capture a sense of searching, of a body in motion, a kind of temporal transience when lines trail off and don’t complete. His style infused itself in mine over time. As I wrote the book, I was constantly searching, archiving, trying to catch something lost, and doing it all through language; this was the same thing my dad and I were doing in those line drawings.

I would never have thought to put the seed drawings on the cover of the book. I’m so grateful to Mary Austin Speaker for creating a design that incorporated them, because over time I love the connection between the poems and the drawings more and more.

DO: How did you decide to include three distinct sections in this collection? How do the quotes that mark each section preface your poems within it?

SDR: Three sections was mostly an intuitive decision; I think I’m instinctively drawn to sets of three (three act structures, I’m one of three sisters, etc.). In earlier drafts, the sections were more thematically and tonally distinct from one another, but as I worked with my editor, we moved poems around and tried to break up the neatness of the sections. We found poems that echoed one another and scattered them more throughout the book, a fracturing effect that made the overall structure more dynamic. At the same time, I do feel like each section contains a new exploration or formal type of poem that opens something new or tunnels deeper into the book’s themes (like the prose poem sequence in section 2 or the titular poem, formatted as a diary entry, in section 3).

As I was writing the book, I collected pages of quotes as possible epigraphs. I kept changing them out, but in the end I chose the three quotes that I found myself returning to even in the quiet moments between writing. The first epigraph is by Alejandra Pizarnik, a major influence on the book and on my writing life: “No cierra una herida una campana. Una campana no cierra una herida. / Close a wound a bell cannot. A bell cannot close a wound.” I was obsessed with the symmetry of those lines, the inversion and mimicry and linguistic play, paired with the rawness of the wound. It resonated with the title of the book and allowed me to dive right into the strange, vulnerable grief of the first poem.

The second epigraph is a set of closing lines from a poem dad wrote in college. “Two thousand feet high we were, / suspended between sky and water, / aware only of our heads.” I loved that poem and had actually worked on a new draft with him a year or so before he passed away. After he passed, I kept those lines with me; the surreal imagery, the sense of suspension, helped me understand my grief. It made me feel connected to him outside of time. As the book grew more intimate and ventured closer to the poems about his death, it felt right to invoke those lines.

The third epigraph comes from the poem “Eros Turannos” by Edwin Arlington Robinson: “As if the story of a house / Were told, or ever could be”. It’s a tempest of a poem, full of fractious yet controlled sound. Those lines, for me, capture the tension and impossibility of rendering the reality of our lives and family stories in language. Especially in grief. Especially when there are pieces of the story missing and beyond recall, especially when there are things we won’t and cannot say. It brought together themes that wove throughout the book, which like a symphonic way to introduce the final section.

The Blue Mimes by Sara Daniele Rivera (Graywolf, 9781644452790, Paperback Poetry, $17) On Sale: 4/2/2024

Find out more about the author at saradanielerivera.com.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.