- Categories:

The Grand Daddy of the Graphic Novel -- A Talk With Will Eisner

The graphic novel genre, or "Graphica," is now estimated to be a $100 million market, one which runs the gamut of subjects: from Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus (Pantheon) to all sorts of Japanese manga (comic books), from Harvey Pekar's American Splendor series to Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics (HarperPerennial).

|

|

Will Eisner

|

The first modern graphic novel, A Contract With God (now published by DC Comics), was created by Will Eisner in 1978. Eisner used the term graphic novel to differentiate his work, which featured mature themes not previously found in comics, as he pitched it to publishers. A Contract With God presented four stories about Jewish immigrant families living in a tenement in the Bronx.

Eisner, who is 84 years old, was creating comics long before 1978. His first professional work was published in 1936 in WOW What a Magazine!, which folded that same year. He then co-founded, with his friend Jerry Iger, the busy comics studio Eisner-Iger. A few years later, Eisner left the studio to work for Quality Comics Group where he began producing a comic supplement for newspapers that included his immensely popular series, The Spirit, about a masked detective with no superhuman powers. The Spirit, which has been widely credited with influencing the work of a number of other artists, including Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (Random House (HC)/Picador (PB)), is currently being published in compilations by DC Comics.

BTW recently interviewed Will Eisner from his home in Florida.

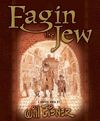

BTW: What drew you to respond to the stereotypical portrayal of Jews by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist?

WE: Over a period during which I was researching popular European folk tales, I became aware that many of our modern day stereotypes originated in early stories. This led me to trace the origin of Fagin, one of the enduring stereotypes of a villainous Jew, created by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist. It attracted my attention because this book has become a children's classic.

BTW: Are there other stereotypical portrayals of Jews, or other groups, in literature that you'd like to address similarly?

WE: There are, of course, other stereotypes in all ethnic groups that warrant consideration. The Jewish ones have been used to hurt, so there is an emergency to their examination. It remains an interesting area for me.

BTW: As you say in the foreword to Fagin, you have your own history with stereotypes, most particularly in the character Ebony White, an African-American sidekick to the Spirit. Although Ebony evolved with greater sensitivity in the latter half of the series' life, do you see Fagin as a kind of response to your own history of using stereotypes?

WE: No, Fagin is not a mea culpa statement. I simply discussed Ebony in the foreword to demonstrate how easily an author can fall into carelessly employing stereotypes.

BTW: In Fagin, and in your other works, the panels, which often overlap and bleed into each other, are generally sketched with intricate representations of characters' faces contrasted against a minimal background. Would you discuss this technique?

WE: The layout of the work is a result of the deployment of images and sequential display rather than in service to page layout. My art, compositions, and sequencing are my way of addressing an adult reader. I tend to depend on the reader's life experience to respond to an impressionistic rendering of a background. The more intricate rendering of faces and body postures are designed to deal with internalization -- or inner emotions.

BTW: When Charles Dickens makes an appearance in Fagin, the mixture of the fictional life of Fagin and the non-fictional account of the Ashkenazi Jews in England in the 1800s blends further. Why did you invite Dickens into an interaction with his character Fagin?

WE: This book was intended as a polemic. The confrontation between Dickens and Fagin is a way of adding realism to an otherwise fictitious character. I also felt it was necessary and fair to show Dickens as he really was, not anti-Semitic.

BTW: You've said that we're on the brink of an industry change. And, indeed, graphic novels seem to be gaining in popularity. What do you think of the current state of the genre, and why do you think it's winning a larger audience?

WE: The sequential art medium that started out as "comics" is filling a need in the ongoing change in communications. Over the last 100 years -- and more pronounced during the last 50 years -- the volume of information has outdistanced earlier forms of written communication. The written text by 1930 had come under siege, and the addition of pictures was necessary to speed up its communication. Words are a powerful communicant and pictures (or images) deliver at enormous speed. The combination of the two -- as in comics -- is the solution for the visibility of modern communication.

BTW: The first graphic novel, Contract With God, seems like a collection of cautionary tales, often with grim consequences for the characters. And some of your other books also broach cautionary or instructive thematic concerns. What do you hope for readers to gain from your work?

WE: I aspire to be a "social reporter," i.e., my stories deal with the human condition and seek to call attention to things that human beings must deal with in the struggle for survival. I'm not a moralist, but I seek out often-unnoticed reality. From this I hope readers will have something to think about. Contract With God was meant to deal with man's relationship with God. The book was initially entitled The Tenement. The original publisher felt that this story was dominant and its title should be that of the book.

BTW: Of course the technology of creating the graphic novel has changed dramatically over the years. How has this affected your work and how do you feel about these changes?

WE: Technology has always had an impact on the arts. For me, the sophisticated reproduction system of modern printing is allowing me to work in greater detail. I still write for "paper-based transmission." I don't believe electronic transmission can yet provide the intimacy and author-reader contact that paper can.

BTW: What are you currently working on?

WE: I'm working on another polemic. A history of an anti-Semitic document.

--Interview by Karen Schechner