- Categories:

A Q&A With Carmen Maria Machado, Author of November’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

- By Liz Button

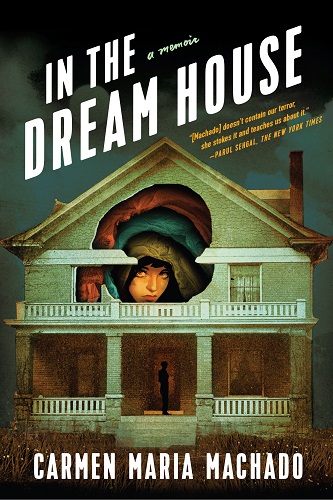

Indie booksellers across the country have chosen In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado (Graywolf Press, November 5) as their number-one pick for the November Indie Next List.

In the Dream House recounts Machado’s abuse at the hands of a charismatic but volatile woman with whom she had a relationship while in grad school. Each chapter is driven by its own narrative trope — the haunted house, erotica, the bildungsroman — in offering essayistic explorations of the relationship and the historical depiction and reality of domestic abuse in queer relationships.

In the Dream House recounts Machado’s abuse at the hands of a charismatic but volatile woman with whom she had a relationship while in grad school. Each chapter is driven by its own narrative trope — the haunted house, erotica, the bildungsroman — in offering essayistic explorations of the relationship and the historical depiction and reality of domestic abuse in queer relationships.

“Welcome to the Dream House in this daring new kind of memoir that defies boundaries and boldly discards the conventions of genre,” said Jason Foose of Changing Hands in Tempe, Arizona. “Inside, Carmen Maria Machado bares her soul in all of its pain and beauty, offering an intimate and profoundly vulnerable look at her own life, love, and sexuality. Machado has a gift for exposing the raw nerves and small miracles lurking beneath the surface of our daily lives. Her words move with a strange kind of urgency, surreal and yet true, like late-night phone calls when the rest of the world is asleep. I didn’t feel like I was reading a book so much as observing a person’s innermost thoughts. In the Dream House is a unique and extraordinary book.”

Machado is the author of the 2017 short story collection Her Body And Other Parties: Stories (Graywolf), which booksellers named number-one on the October 2017 Indie Next List. Her Body was also a finalist for the National Book Award and won the Bard Fiction Prize, the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, Electric Literature, Tin House, Guernica, and the Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy, Best Horror of the Year, and Year’s Best Weird Fiction series. Machado has an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has been awarded fellowships and residencies with the Elizabeth George Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, Hedgebrook, Yaddo, and more. She is the Writer in Residence at the University of Pennsylvania and lives in Philadelphia with her wife.

Here, Bookselling This Week speaks with Machado about her second book, which has so far received starred reviews in Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, and Booklist.

Bookselling This Week: Why did you decide to write this memoir and why now?

Carmen Maria Machado: It’s such a simple yet complicated question. I’ve been trying to write this book for a very long time, and I think what happened was a kind of confluence of events after Graywolf bought my first book. I had some time at some residencies where I was finishing up Her Body and Other Parties, and I had spent the in-between time working on the memoir. And then when Graywolf asked me if I had anything else, I said, I do actually, I have this weird memoir that I feel like would be perfect for you guys. So I feel like a lot of things came together. I think if I had written it earlier it wouldn’t have been as good, and I think if I had tried to sell it before I sold Her Body it wouldn’t have sold.

BTW: In the book, you write, “The nature of ‘archival silence’ is that certain people’s narratives and their nuances are swallowed by history. We see only what pokes through because it is sufficiently salacious for the majority to pay attention.” How do you think you would have benefited from seeing more books, movies, and other cultural representations of domestic abuse in LGBTQ relationships when you were younger?

CMM: It’s hard to posit how my whole life would have been different. If those kinds of narratives had been in my mind even before I met this woman, I wonder if it would have been more clear-cut to me. Maybe it wouldn’t have, maybe the same thing would have happened. But also I think that afterwards, when it was over, I was really struggling to find a context for myself, and once I started putting language to it, I sort of realized what had happened and in a weird way, how mundane it was. When you don’t use gendered pronouns to describe what happened, it is very clearly an abusive relationship; that’s not even a question. It only becomes confusing when suddenly you’re like, what does it mean that I was abused by a woman and not a man, as a woman? It’s complicated. But I do wonder what it would have meant to have had context, in the same way that I wonder what it would have been like to have had narrative context when I was a young person who didn’t quite know that she was gay or queer.

BTW: Each chapter of the book features a different narrative trope (Dream House as “X”), including Dream House as spy thriller, as diagnosis, déjà vu, the apocalypse, haunted house, bildungsroman, Choose Your Own Adventure, and even as an original fairy tale, “The Queen and the Squid.” Why did you decide to write it this way?

CMM: I would be lying if I didn’t say it was more manageable as a text, but I also think there’s something to be said about the shape of the book honoring the contents. I really struggled for a long time both because I didn’t have the distance from it that I needed, and because I was trying to tell it in a straightforward way and it’s not a straightforward story. I think that it’s sort of this process of defamiliarization; everybody here knows this is a story of domestic violence, but what does it mean to back up and tell it in this way that reflects the inherent brokenness and the inherent trauma of the experience? And I feel like once I lit upon that form, the whole thing opened up in this way that was really meaningful to me.

I knew I wanted to center it around the house, because I’m really interested in haunted houses and architecture and those different spaces, and so much of the story happened in the context of that house where we lived in Indiana and other houses. And the idea of the house has so much loaded terminology when it comes to domestic violence, so I knew I wanted it to serve as a sort of visual metaphor. So after ruling out the working title, House in Indiana, I went through all these titles and thought, well, what about the Dream House as a concept? I think it operates on these different levels: building your dream house, a Barbie Dream House, a house of dreams. There are just a lot of moving pieces to the title which I think works.

BTW: In the book, you refer to the Motif Index of Folk Literature to create footnotes that illustrate the different allegorical aspects of the story. That same pull toward fairy tale and folklore is echoed in parts of Her Body and Other Parties. How did your interest in this area first come about?

CMM: As a kid I had a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale book and the stories in there are really f***ed up, which you know if you’ve ever read Hans Christian Andersen. They’re weird and they’re kind of dark. Like The Little Mermaid! As a kid I liked stories that were a bit scary or disturbing even though I was a big coward, a big chicken. I was afraid of them but I also moved toward them, and I feel like that is kind of my personality in a nutshell. So it started fairly young, I think, like a lot of kids. I was attracted to the darker elements of fairy tales and urban legends and folktales. I also had this book as a kid called The Dark-Thirty, which were these weird ghost stories from the South that I just loved.

The thing about fairy tales and myths and folklore is that you can sort of categorize them, and there’s this really interesting taxonomy associated with those stories. Looking at this idea of, what does it mean to be living in a story that is kind of a cliché? And then how do you subvert that cliché and how do you move around it? So for me, folktales have so much to do with these different categories, but then at the same time, you can really look at them in new ways and open them up and turn them inside out and see what they actually mean, even in the context of their own familiarity.

BTW: In the Dream House features the splitting up of your point of view into “you” and “I” sections, illustrating the fracturing of the self as a result of trauma. How did the decision to do that come about?

CMM: The funny thing is that when I sold the book it was written in the second person, and I barely registered that that was true. I didn’t do it on purpose. And my editor said, when we’re ready to work on this with you, something we might want to talk about is this second person perspective: what’s happening there? He thought that because I just wrote it that way automatically it might have been some kind of trauma response, and he asked if I could just look at it, and maybe explore that creatively, and I said, cool, sure. So I went back to it, but a lot of the pages that I had already written lost all their energy when I read them in first person. So I had an idea; I was thinking a lot then about Justin Torres’s We the Animals. It’s this stunning novel that has this really traumatic gut punch of an ending where the perspective becomes fractured, and I thought that was so devastating and so beautiful. I was really moved by it. And I thought, what if I actually do this very conscious thing where I split apart the perspectives? And that really did make the whole thing sync up.

BTW: You’re currently on your second book tour. Her Body and Other Parties was a bestseller, received numerous awards, and is currently being made into an HBO show. What has this whirlwind journey of success been like for you?

CMM: It’s been amazing. Obviously, I am deeply grateful to indie booksellers. They have been selling my book like crazy, selling it everywhere. I never in my wildest imagination could have ever guessed it would happen. I really thought I’d be lucky to make back my advance with that book, so for anyone to have read it...I feel like the success of it still sort of surprises me and I don’t really know what to make of it exactly. Even though honestly, it makes me super happy. It’s just been incredible and a little overwhelming. For the last couple of years, I’ve been adjusting to a new life, a new way of being and a new way of living, and of organizing my time and my practice as a writer. I can hardly believe I’m heading into a second tour. I think this is something that happens to a lot of writers where they can imagine writing their first book but getting past that book feels impossible, and I felt that, too. But there has been this sense of forward propulsion that I think was made possible by the success of the first book.