- Categories:

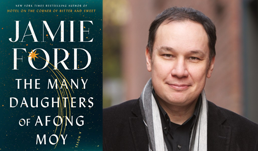

A Q&A With Jamie Ford, Author of August Indie Next List Top Pick “The Many Daughters of Afong Moy”

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Jamie Ford’s The Many Daughters of Afong Moy (Atria Books) as their top pick for the August 2022 Indie Next List.

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Jamie Ford’s The Many Daughters of Afong Moy (Atria Books) as their top pick for the August 2022 Indie Next List.

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy follows Dorothy Moy, a former poet laureate struggling with her mental health, as she connects with past generations of her family through an experimental treatment for inherited memories of trauma and love.

“Jamie Ford explores the relationship of mind, spirit, and personal history in this gorgeous, multigenerational novel,” said Beth Mynhier of Lake Forest Book Store in Lake Forest, Illinois. “The descendants of Afong Moy dig into their inherited pasts with astonishing results. A hopeful, beautiful read!”

Here, Bookselling This Week talked about writing the book with Ford.

Bookselling This Week: Epigenetics is a fascinating and complicated topic to explore. Can you share more about why epigenetic inheritance was a key influence for the novel?

Jamie Ford: It began with Afong. I have known about Afong, known her story, for at least a dozen years. And I wanted to explore that in fiction, but there just wasn’t enough of a story there that I thought to build a whole novel around. But once I had read an article that was from Emory University about epigenetics, about how one traumatic event was transmitted across several generations,I looked at the character of Afong and realized I could give her descendants. All those descendants could inherit in many ways the trauma that she went through — the abandonment, the isolation, just feeling alone in the world. And it could ripple through many generations and tell a much larger story.

Much of the research regarding epigenetics, the longer version is transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is about traumatic events. It’s about pain. It’s about the things that we were exposed to that were negative. And from a research standpoint, those things are much more easily recognized, whereas things that are more benign or beneficial are perhaps harder to see. I looked at it and thought, we inherit pain and trauma, what else can we inherit? Can we inherit an emotional IQ? Can we inherit stronger empathy muscles? Can we inherit things that help us interact with other people — our ability or inability to love other people? And the epigenetic love story unfolded from that premise.

BTW: This is your first time diving into speculative fiction in a novel. How was the experience and do you see yourself writing more in the future?

JF: I have so much success with my first book, which is historical fiction that I stayed in that world for a while. But much of what I’ve read growing up and what I still read might be considered speculative. I see more literary authors now just kind of kicking the wheels of convention off and really blending genres and crossing genres, and I always wanted to do that. I didn’t do it in a mechanical way, I just wanted to write the story I wanted to write. Where it fell on the bookstore shelves, I’ll leave that up to other people. But short fiction is where I’ve written crime noir, I’ve written steampunk, speculative fiction, dystopian, middle grade horror. It’s nice just to be able to — I want to write all the things. I don’t want to be stuck in a box, per se.

As I was writing this book, it was so much more complicated than anything I’ve ever written, on several point of view characters and different timelines, and it’s historical and speculative, and it’s got a lot of science, it’s got some philosophical stuff. As I was writing it, I just promised myself, I’m like, okay, the next book is going to be contemporary, have one point of view. I’m going to make it so simple. And then when I sat down to start a new book, I just had too many rabbit holes of curiosity that I tumbled down and then I want to write about and I feel like this is a tough book to tame. With my first four books, my first book was my freshman book, and this is my senior book, if you will, and I’m ready to graduate, get out in the big world, and figure out what I’m gonna do when I grow up.

It was pretty ambitious. I wasn’t sure if I could stick the landing even after my editor loved it. I wasn'’ sure if maybe she thinks I’m a Make a Wish Foundation kid, she’s just being nice but the real news would come later that it’s not working. Honestly, it was one of my best friends — when I told him I wanted to write something simple, he’s just like, you’ve got to keep challenging yourself. You don’t want to bump up against adversity in writing and simplify your writing over time. Even if I fail, as in the Teddy Roosevelt quote, “at least fail while daring greatly.”

BTW: The story follows the lives of six strong women with their perspectives in a particular time in history (and a bit of the future). How do you write them as relatable characters that readers are invested in throughout the whole novel?

JF: As far as making them relatable, it sounds terrible, but you have to be a mean God. The more you torture your characters, the more people want to see them have measures of comfort and relief. If I didn’t torment them so much, people would be less interested. But fundamentally, when I wrote all these characters, I did see all of them as echoes of Afong. They’re all genetic expressions of Afong occurring at different points in time. They have some of the baggage and personality traits, but then their environment, their modern context, has changed them, so they’ve evolved and grew up differently. Each woman is a woman of her time. And sometimes she fits into that world, and sometimes she doesn’t. But fundamentally, it’s kind of the same character, if you will. They’re not literally the same character, but genetically they are. You can only run so far from your genetics.

They all have problems but their problems are reflective of their time. Some of them are explicit racism and bigotry and things like that, and other ones are just trying to fit in. Even within your own family, which can be a challenge.

I think of writing as banking and spending emotional currency with the reader. When you toss nails in the paths of your characters, you’re banking some emotional currency, and then you’re going to pay it off at the end — in a good way or a bad way or whichever way you want to take it as an author. But there’s going to be an emotional endpoint, and I always write with that in mind.

BTW: In each of the characters’ stories, there is social and political commentary infused such as mental health, sexism, racism, and LGBTQ+ issues. Can you talk more about your inclusion of these topics and their part in history?

JF: I want to be representative of the time. It wasn’t like it was a grand design, where I’m checking boxes, but I did want to explore what it means to be an Asian American, or specifically a Chinese woman, in all these time periods. For Afong, she is monetized for her otherness and exoticness. With each generation the circumstances change and get a little better, but there’s just different obstacles. With Zoe in England at the time, people think of the Suffrage movement as we’ve crossed the finish line and everything was better. But even in England at the time where women fought and had hunger strikes for Suffrage, they couldn’t vote unless they were married.

There were still these institutionalized problems and I didn’t have to look very far to find them. They’re so commonplace, and it was nice to show the difference. I can show this very innocent crush between Zoe and her teacher, a coming-of-age story with a young queer character. And then in Dorothy’s time she has best friends who are a married queer couple. Things have gotten better and things have evolved. And I think much of the story is about the characters, but it’s also about [how] each setting has changed. There's a little bit of a leap forward and a little bit of a leap back.

But sometimes people — there’s so much going on. Like the changing weather patterns in Seattle, I didn’t try to write a morality play on global warming or anything like that. I just thought it’d be interesting that, from the character standpoint, the background of weather in Seattle — which is always part of its personality — has just been taken to the extreme. It’s nice to look at some of the early reviews and no one has taken it as some sort of moral treatise on global warming. That was never the intention. It was just to heighten the drama and to touch an adjacent reality that is near future. I wanted to write about possible futures, if you will.

BTW: Can you talk more about your process of writing and honoring your Chinese American ancestry and heritage?

JF: I really believe we’re in this golden age of cultural cross pollination in fiction and cinema, where we are learning and appreciating the experience of other people. People of color historically have had different problems, different challenges, and many of the stories of those challenges and struggles have been kept within those communities until the last 20 or 30 years, where suddenly every book on the shelf isn’t a problem of a Eurocentric couple. It’s the story of someone who’s come to this country from Pakistan or Greece, or from China or Bahrain. There’s all these stories just waiting to be told.

I am half Chinese and half Caucasian, I could tell stories that were perhaps inspired by my mom’s side of the family — the Caucasian side of the family — but there are other people doing that. And as a mixed race person, I have a different perspective and am more inclined to write about those things if for no other reason than just self-exploration, to have a better understanding of myself. Writing Chinese American characters brings me closer to my Chinese American family. My father spoke Cantonese fluently and has since passed away, and it’s a way of honoring them and honoring their struggles. Every generation is built upon the struggles and triumphs of the previous generation. But if the previous generation had to deal with racism or sexism or bigotry, they just had struggles that other people may not have been encumbered with.

BTW: You’re about to begin your book tour! How have independent bookstores played a role in your life?

JF: I owe my career to indie bookstores. Truly. It’s wonderful to be a bestselling author, whatever that means. But indie bookstores are reality. They’re what booksellers are reading and recommended to their readers, they’re what readers are coming in and asking for. They’re not the dictates of a large retail corporation and they’re not affected by co-op. It’s a more honest, more pure system that comes from an ecosystem that’s created by independent booksellers. It’s real, it’s tangible, it’s substantial. When it comes to going out on tour, I do go out of my way to visit as many indies as I can, either for an event or for a stock signing. For my first book we drove from Bellingham, Washington, down to California and we hit every indie store on the way just to pop in and do stock signings and say hi to people.

Bookstores matter. I did a tour on my own for Central Washington to places like Leavenworth, Wenatchee, Moses Lake, and Yakima, and [there are] just tremendous bookstores that are anchors of those communities. And as an author, I think you need to feed your own community, and my community are indie stores. In Montana, my publisher is sending me to the bigger markets but it’s well known to them and to my friends at my stores here that I’m gonna go to Bozeman and Missoula and the new store in Great Falls.

Those stores, they matter. I don’t have any kind of success on my own outside of that ecosystem. It’s just impossible. My career is built upon that support.