- Categories:

An Indies Introduce Q&A With Doma Mahmoud

- By Emily Behnke

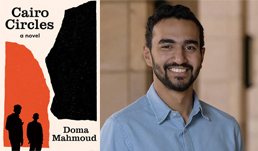

Doma Mahmoud is the author of Cairo Circles, a Summer/Fall 2021 Indies Introduce adult selection and October 2021 Indie Next List pick.

Cairo Circles follows the intertwining lives of six characters, revealing complex relationships dominated by faith, tradition, social class, and the boundaries of personal freedom.

“How can we figuratively and literally go home again once we've expanded our circles? How do we reconcile our inner states and desires with those projected upon us by society and family?” said Amanda Qassar of Warwick’s in La Jolla, California. “In Cairo Circles, Doma Mahmoud gracefully explores how expectations — socioeconomic, cultural, emotional — both separate and bring us together, how our circles are both cuttingly drawn and ineffably fluid, intersecting and refracting, creating complex new geometries of being. Mahmoud manifests these soul-jostlings through a cast of characters rendered with incisive sympathy, beauty, and humor — compelling, real characters that linger long after the last page.”

Here, Mahmoud and Qassar discuss music, postmodernism, and more.

Amanda Qassar: Cairo Circles starts with a straight-up nightmare scenario for an Arab-American: Sheero, a college student from Egypt living in New York, finds out a close relative has committed a deadly act of terrorism. Did you always know this would be the initial scene sparking the action? If so, why? And if not, how did it evolve to become the beginning of the story?

Doma Mahmoud: I decided to include terrorism in the novel pretty early on. The first reason is that terrorism carried out supposedly “in the name of Islam” has always had horrible consequences on my life. My sister and I were the only two Muslims in my entire primary school in Madrid when 9/11 and the 2004 Madrid bombings occurred. It was tough. I also come from a fairly religious Muslim family, and it has always baffled me that the same “Allahu Akbar” my parents and grandparents say when celebrating a marriage, soccer goal, or delicious meal could be uttered in the name of violence. So, it was personal history and curiosity on one level, but then, on another level, it was just frustration. Across literature and film — in works like Taxi Driver, American Psycho, Narcos, etc. — we’ve seen violent people written about with empathy and nuance. I found myself crying during that scene in Narcos after Pablo Escobar’s cousin gets killed. Then I remembered: Wait a minute, these guys are cold-blooded killers! But I think it’s important for literature to highlight the humanity of people who do horrible things, so we can better understand, detect, prevent, rehabilitate, what have you. Whatever the reason, it hasn’t really been done with radicalized Muslims, not in contemporary film or fiction; so I decided to give it a shot. It ended up being Sheero’s close relative that is radicalized, and his thread of the novel always began with the attack. Sheero is forced to try to figure out/remember how it came to be. It also thrusts him into his arc.

AQ: One of your research interests in your work at the American University in Cairo is postmodern fiction. Can you speak to how that mindset influenced or manifested in your writing? (Lest anyone reading this cringe in horror at the “PoMo” word, have no fear — Cairo Circles is a highly readable novel that, as Jonathan Safran Foer neatly puts it, “proves literature needn't choose between pleasure and substance.”)

DM: The dreaded PoMo! I have to start by saying that that’s just something that was put on my faculty profile online to make me look "academic." I should probably get someone to remove it. That being said, my literary education happened almost exclusively in America, where I moved when I was sixteen, and I was indeed made to read a lot of postmodern literature in class. As a writer, I appreciate the way the postmodernists tore down previous notions of how a novel should flow or be structured. Cairo Circles is circular and fragmented and follows five points of view. That being said, a good amount of the fiction being published today rejects some of the main attributes of what we consider postmodern. Writers are making political and philosophical statements in their fiction about meaning and truth, and I think I do that in Cairo Circles. Will I stand by each of these statements forever? Probably not.

AQ: Cairo Circles is full of distinctive, richly developed characters that I continue to think about long after reading the book. Did any or all of your characters precede the plot, or did you bring them to life in service to telling a certain story?

DM: Thank you! A vague idea of the characters preceded the story. The rich kid and his nanny, who basically raises him. The nanny’s own children. The kid who comes from a middle-class background but goes to school with the children of Cairo’s bourgeois. These were people I had come into contact with in my life. But it was through figuring out the plot that the characters developed personalities.

AQ: Music is a distinct presence in this book, appearing in scenes of tension between generations: a girl dreaming of a less restrictive life sings “Enta Omry” (“You Are My Life”) for her mother's rich employer and party guests; a boy is punished by his father while the refrain of “Ya Noor El Ein” (“Light of My Eyes”) plays on TV. Songs like these are ingrained in me, but much like characters in Cairo Circles, I also grew up with and deeply love a lot of Western music. Can you discuss the role of music in this book, and in general when it comes to its force as both a bridge and a barrier?

DM: I’m one of the people whose memory is really engaged by music and sound. Smell does little for me. I can even look at a photograph of myself at a place I once considered home and feel like I’m looking at someone else. But a song will immediately take me back. For most Arabs, the soundtrack of the late nineties is Amr Diab. It was an easy way to mark the time. And to take myself back as I wrote the scene.

I saw something fascinating a few months ago. I was shopping for groceries in Cairo, and one of the workers at the store, a grown man, was playing Billie Eilish on his phone and singing along as he sorted out items on a shelf. I could tell he could barely speak English because he was messing up the words and turning them into gibberish, but it didn’t matter. He likes how Billie sounds. Music mostly serves as a bridge between people. That working-class man at the grocery store likes Billie Eilish, and so do the students who attend the city’s most expensive private schools.

AQ: Cairo Circles portrays family dynamics in a voice both affectionate and acerbic. So much of the action revolves around failing to be circumscribed by the expectations of society, friends, family, and elders. How does your own family feel about your accomplishments as a writer?

DM: It’s been a journey. There’s an inherent risk in trying to be an artist. That risk is oftentimes even higher for immigrants, POC, and anyone from a more collectivist society. You’re likely to fail, go broke, and render pointless the long list of shocking sacrifices your kind parents made to give you opportunities they themselves didn’t have. I recently saw an SNL skit starring Daniel Kaluuya during which first-generation immigrants scold their son for switching his major from pre-med to creative writing. At first it made me laugh, it was so similar to a once recurrent scene from my own life, but then I got really, really sad. I thought of all the times I almost caved under my family’s pressure to take another path and write on the side (whatever that means), and everything I would’ve lost out on if I had. I’m so grateful I didn’t, because the process of writing and publishing this novel has given me so much life. My parents are happy to see me being published and read, but their risk aversion persists. What now? Who’s to say I’ll be able to write anything else? Being a writer has brought me great teaching and freelance jobs, but they’re still skeptical and anxious. When I was younger I used to conflate their anxiety with mean discouragement, but now I try not to take it personally. They just can’t help it.

AQ: Is there any one lesson, or perspective, or even just a feeling that you hope readers take away from Cairo Circles?

DM: It’s hard to pick one. It also depends on the reader. “Check your privilege” is a phrase that has been passed around a lot, but I think that’s something I hope the book does for people: makes them feel the weight of their being far luckier than others for no good reason, almost to the point that it hurts. I think it makes us better people to feel the weight of it, even if it’s just for a day or a moment. It certainly does for me. Finally, I hope readers are engaged by the drama in the book. I live for novels that are dramatic and hard to put down, and I tried to make one in Cairo Circles.

AQ: What are you reading now, or, what have you read recently that you loved?

DM: Another city I’ve recently spent some time in and developed feelings for is Beirut. I’m currently reading Rawi Hage’s De Niro’s Game, which is incredible.

I also loved Asako Serizawa’s Inheritors. In the right hands, a book can be gigantic in a way a film can never be. It can make huge leaps across time and space, shift from character to character at will, and, ultimately, present the reader with a sharp portrait of a nuanced subject matter, which Serizawa does brilliantly in Inheritors, with 20th century Japan and its relationship to colonialism and war.

Cairo Circles by Doma Mahmoud (Unnamed Press, 9781951213367, Hardcover Fiction, $28) On sale: 10/12/2021.

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.