- Categories:

A Q&A with Jeanine Cummins, Author of February’s #1 Indie Next List Pick

- By Emily Behnke

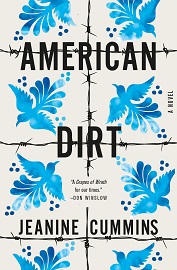

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins (Flatiron Books) as their number-one pick for the February 2020 Indie Next List.

The novel, which has been hailed by early reviewers as “a Grapes of Wrath for our times” and “a new American classic,” centers on Lydia Quixano Perez, a bookseller in Acapulco, Mexico, who is forced to flee the city with her son after a violent day changes the course of their lives. The two, now migrants, must navigate a treacherous series of freight trains coined “La Bestia” to get to the U.S.-Mexico border as quickly and discreetly as possible.

Thatcher Svekis of DIESEL, A Bookstore in Santa Monica, California, called American Dirt “a beautiful, heartbreaking odyssey, a vivid world filled with angels and demons, one I only wanted to leave so I could get my heart out of my throat.” Said Svekis, “Cartel violence sends a mother and her son careening north from Acapulco toward the relative safety of the United States, and every moment of their journey is rendered in frantic, sublime detail. Danger lurks around the corner of every paragraph, but so does humanity, empathy, and stunning acts of human kindness. You will feel the toll of every mile, the cost of every bullet, and the power of every page. A wonder.”

Here, Bookselling This Week and Cummins discuss how she came to write this novel.

Bookselling This Week: Where did the idea for this book come from?

Jeanine Cummins: The first moment I felt like I should write about this happened many, many years ago, when my husband, who was my boyfriend at the time, and I were vacationing in California. We had taken the week to drive the Pacific Coast Highway and our last stop was San Diego, and one day I drove down to the border by myself. My husband was an undocumented immigrant and I didn’t want him anywhere near the border, but I wanted to go and just see it. And I accidentally drove into Mexico, which you could still do then. It was pre-9/11 and the border was not militarized the way it is now.

I’d been to Mexico before, but I’d never been to the border. I was so shocked by what I saw there. There were so many young men with only one leg. There were young kids trying to sell gum or hats or piñatas or whatever touristy stuff they had to sell. I had no money because as soon as I got there, I got pulled over by the policía and they took it all. The fine print on my rental agreement said I couldn’t have the car I was driving in Mexico, and the officer said he would impound the car and I would have to wait in jail for a few days to talk to the judge. I was 21 or 22, and I was terrified. I said I couldn’t go to prison, and he said, well, maybe there’s another way. You can pay a fine. And I said, how much is the fine? And he said, how much you got?

I gave him all my money, and then I waited five hours in line to get through U.S. Customs and Border Protection to get back into the United States. After crossing accidentally in seven seconds. So, I was sitting at the border for many, many hours, just observing all these young kids, and I must have seen five for six young men with only one leg. And I didn’t understand what I was looking at. When I got home to New York, I started researching. I came across “La Bestia,” and I came to understand that these were men from Central America and southern Mexico who had, in all likelihood, ridden the train to the border and had fallen off at some point and been maimed. I came to understand how common this was, that it’s happening every single day. In the effort to just reach the U.S. border, never mind cross it, people are being killed and maimed daily. It’s commonplace. And I was like, why don’t I know about this? Why don’t people in the U.S. know this story?

I never stopped thinking about that, and for many years, I felt an enormous reluctance to write about it. I felt, very clearly, that it just wasn’t my story to tell. And even when I started thinking about writing about the border, I resisted writing from a migrant’s point of view for a long time. But if I really wanted to get into it, then the correct thing to do was to tell the story of the people who were suffering.

BTW: Your author’s note mentions that you began writing this book in 2013, when the conversation about immigration in the U.S. was very different. Did the 2016 election influence the story you originally set out to tell?

JC: It was less influenced by the 2016 election than by other factors, believe it or not. The fact is that this story, unfortunately, pre-dated the current administration and it’s going to be here when they’re gone. The tenor of the national dialogue has shifted into a place that feels a bit more cruel, I think, and we’ve had this sort of resurgence of casual racism in this country where it’s cool to say things again that for decades we had stopped saying out loud. I think the current climate in the country socially has been to bring all of our dirty laundry back out of the shadows and hang it up in the breeze again where we can see it. But it was always there.

There were a number of factors that altered the book, with the first and the biggest one being my research. I took a couple of years to watch every documentary I could find and read every book I could find while I was drafting the first terrible version of this book. As soon as I went to Mexico, I threw out everything I had written and started over. It’s one thing to learn academically about the statistics of the people who are being maimed and killed on “La Bestia” every day, and it’s quite another thing to walk into a migrant shelter in Tijuana and see a young man who lost his leg three days earlier. The experience of meeting migrants and listening to their stories from their own mouths and meeting the people who have dedicated their lives to supporting them was hugely influential for me.

Frankly, another huge factor that is incredibly personal is that my father died a week before the 2016 presidential election. He was Puerto Rican, and our president is no big fan of Latino people. It was this double whammy of losing my dad at the moment when this country felt so viciously divided in a way that I’d never seen before in my lifetime. I think there’s a way in which grief, really debilitating grief, can eventually function as a springboard. There are so many missing fathers in this book — every single character is grieving for their father — and that was a thing I didn’t realize until the book was over. As I was writing it, all of that grief was mine in real time.

I’ve had significant trauma in my life before, I’ve written about it before, I thought I knew how to grieve, and then my dad died and I could not function. I didn’t write. I couldn’t even read. I didn’t have the reservoir of emotional space to take words in or produce them. I didn’t do anything for about four months, and then in February 2017, I just dragged my laptop into bed with me and I wrote the opening scene of American Dirt. I knew that everything I’d written before was wrong. I knew that this was the book. I started over completely, and I wrote the whole book in about 10 months.

I’d been steeping in the research for four years by then. I knew the characters. I knew their stories. But the way I had been writing it was so reserved, and I think my grief propelled me into the story in a way that would never have happened if my father had not died.

BTW: How did you craft Lydia’s character?

JC: She’s a lot like me. The elephant in the room is that I’m not Mexican. But she’s a mom and I’m a mom. The experience of the parent-child bond is not universal, but it’s global. It’s something almost everyone can relate to because we are all either parents or the children of parents. Most of us are the children of parents who love us, so we know what that looks like, and we know what the fierceness of that kind of love feels like from one side or the other. And that is the lens through which I feel comfortable telling this story. Because the fact is that Lydia is Mexican. And though she lives in Mexico, she lives a life very similar to mine. She is a comfortable middle-class woman who has a husband she adores and a child who she loves with utter devotion. Because she is those things, it was quite easy for me to imagine myself into her life with all of the research that I did. At the end of the day, the whole point of the book is that she can be from anywhere — she can be from Afghanistan or Africa or Australia right now.

What would you do if you lived in a place that began to collapse around you? How would you save your kid? The answer to those questions crosses every single cultural border. We would all do anything to save our kid.

BTW: During her journey, Lydia must decide if she and her son will risk the dangers of taking “La Bestia” to get to the U.S. How did your research impact Lydia’s decision to take these freight trains?

JC: Research-wise, most Central American migrants who are coming to the U.S. now will come by a series of coyotes. They’re coming through almost an underground railroad system, and they’re travelling all the way from Honduras or Guatemala. They’re being driven sometimes on buses with false papers or in someone’s family vehicle. But given how quickly Lydia’s exodus was from Acapulco, and the fact that she didn’t have time to plan for a coyote or to gather Luca’s birth certificate and the travelling papers she would need, I believe “La Bestia” would be her only route.

The majority of Mexico is incredibly safe. The problem is that if you do find yourself on the wrong side of a violent criminal, there’s very little recourse, because there’s so much corruption in the police force that you can’t rely on law enforcement to protect you or to give you help. Very often, your only recourse is to run. Especially in a situation like Lydia’s, travelling from place to place on extended stretches of highway between states, is incredibly dangerous in Mexico, depending on the state and the route.

There are currently 40,000 people reported missing in Mexico. Law enforcement authorities there pretty routinely find mass graves, and those mass graves are largely believed to contain the bodies of migrants. So, even if Lydia was an anonymous migrant, even if she wasn’t someone who was being actively searched for by the head of a cartel, being a migrant on the highway is incredibly dangerous. You can’t travel by road, is the bottom line. That’s why so many people are travelling by foot, or “La Bestia.”

BTW: On your website, you mention finding “a preponderance of hope among people who endure so much hardship” when conducting research for this book. How did this hope manifest?

JC: One of the most influential things was how much compassion I saw — and it was the most surprising thing to me, too, how much kindness and goodness, bravery and solidarity exists among the migrants and the people who have devoted themselves to protecting them and helping them. I don’t even know how to describe the effect it had on me emotionally. It made me feel ashamed of our country, but more than that, it made me feel such hope for humanity.

In recent months, it has begun happening that in addition to all of the other terrifying things they have to face on their journeys, these migrants are now being hunted, in some cases, at the shelters. The priests who are running these shelters are putting themselves in between the authorities, who very often aren’t really the authorities but have nefarious intentions for these migrants, and they are being the shield and standing at the door saying, you shall not pass. To see that over and over again was so incredibly inspiring, and it made me feel good about humanity, that whatever awful stuff was going on out there, there are so many people who not only want to do the right thing, but who are willing to risk themselves in the service of protecting vulnerable people. I wanted to make very, very sure that message was clear in the book — how much goodness I encountered not only in the migrants themselves, but along the migrant trail.

BTW: Is there one thing you would want readers to away from this book?

JC: Very simply: migrants are people. In this country, it’s so difficult to have any kind of open conversation about immigration because the second we open our mouths, we have to choose a noun. We choose migrant or alien or immigrant or refugee or undocumented or illegal, which are crazy adjectives that have become nouns. As soon as you choose your noun, the person on the other side of that dialogue rolls their shutter down, because they know where you stand. The conversation is over before it begins.

The great thing about fiction is that it can liberate you from that. It can afford readers the opportunity so now they don’t have to choose a noun. They can just talk about these people by their Christian names. They can talk about Rebecca and Soledad and Lydia and Luca and Javier and Lorenzo and everyone else who they meet along the way, and they don’t have to label them. They are just like us, like any other people. Some of them are assholes, some of them are incredibly talented. Some of them are geniuses, some of them are beautiful, some of them are painters or singers or doctors or scientists.

They’re just humans. Labelling them from the get go as migrants or whatever other word we use is part of the reason we are in the mess we are in policy-wise in this country. We have forgotten that we’re talking about human beings.